|

Chapter

15

You

Are The System

We’re nearly ready to do something

monumental, but not quite.

I used to manage IT systems for a key

component of the global economy (it makes me feel a bit gloomy that I knowingly

helped prop up Industrial Civilization for a while, but more of that later) and

whenever a major piece of work was due to be carried out I would first analyse

all of the stages of the task, finding out where problems might occur; I would

then assemble a team of people to help iron out any of these flaws and identify

any other potential problems I might have missed. There were always one or two

small things I missed, right up to the day of execution; and usually things that

we had to deal with “on the fly”: no plan is perfect. That said, if a great

deal of effort went into the planning process, the work was likely to be far

more successful than just plunging into it, hoping everything would go fine.

So, here’s the plan: first, I want

to go over a few key points, just so they are absolutely clear in your mind, no

question; second, I want to go through the approach I have taken, in creating

what I think is an effective solution. The reason for this transparent thinking

is mainly because I don’t want you going into this as an unwilling partner. So

many so-called environmental “solutions” assume that the reader / watcher /

listener will blindly obey whatever tasks are set before them, leading to an

outcome where the burnished sun sets over the shimmering sea, and we all march

off into Utopia arm-in-arm.

It doesn’t happen that way.

I’m not saying the outcome won’t

be far better than what we have today (it can hardly be worse) but I am in no

mood for half-measures and want something that actually does the job of fixing

the problems we face; not putting little green sticking plasters over the

expanding cracks. What I am going to propose is radical, fundamental and

frightening. It is also long-term, exhilarating and absolutely necessary. I

would much rather scare people off who are not ready to make the commitment for

a change of this scale than pretend they will be able to fix things by changing

their electricity supplier, upgrading their cars and enlisting their friends in

an orgy of “greensumption”.[i]

Transparency is the by-word, then. By

reading this chapter you will understand why I have proposed what I have later

on in the book. If you don’t like my train of thought then you could try

reading Chapters Seven, Ten and Eleven again and see if they clarify things; if

that fails then put this book down and come back to it in a few months time.

Before you do anything, I want you to feel comfortable in your own mind with

what lies ahead.

Your

Part In All This

In Chapter Thirteen I went some way

towards describing how Industrial Civilization operates; in particular the

methods used to make sure people are no threat to the dominant culture, and an

explanation of where the power really lies. If you were expecting a conspiracy

theory, which placed the elite members of society in some unassailable position,

guiding our every move, then you probably ended up disappointed. Yes, the rich

and powerful do get a lot more material benefit from this unequal setup, but

they are also teetering on the brink of psychosis whenever the power rush gets

too much. There are an increasing number of people who subscribe to “New World

Order” theories and the like; ideas that seem very appealing when you are

stuck in a dark place, trying to get out. The Internet is awash with conspiracy

sites[ii]

describing in minute detail every cartel; every meeting; and every deal that

takes place to ensure power is kept with the people who already have it. The

complex structures that actually exist to ensure economic growth continues are

benefiting greatly from this paranoid activity.

Here’s one example: suppose there

is a large trawler that comes into port, day after day, its hold brimming with

fish. Time passes and the size of the other crews’ hauls begin to diminish, as

the fish stocks are gradually depleted. The local population starts to become

concerned about their future. One of the locals proposes a theory that the

successful skipper is getting information about fresh shoals of fish from some

mysterious source who has knowledge far beyond their understanding: a

supernatural force, perhaps. This idea becomes accepted fact. Whispered

discussions about this “higher power” fill the inns for many nights, but

nothing is ever done because there is nothing that can be done to defeat

such powerful entities. Meanwhile, the successful skipper continues to bring

home heavy catches, and the fishing stocks keep getting smaller.

It turns out that the successful boat

is actually equipped with a better form of sonar than all the other boats,

imported from another country where it is already widely used. This being a

small isolated fishing port, nobody else is aware of this new technology. Had

the other crews taken time to look closer to home and cleared their heads of

“higher power” thoughts, then they would have realised that one boat simply

had better equipment than all the others. In order to protect the fishing

stocks, their simple task then would have been to sabotage the sonar on the

successful boat. Every time that sonar was repaired, they would sabotage it once

again.

Ignoring the fact that the law may

have eventually caught up with the saboteurs – after all, the law exists to

maintain economic success above anything else – their efforts in attacking

the immediate cause of the heavy catches would have prevented the fish stocks

falling for a while; but then other boats in other ports may have started to use

this sonar, hitting the stocks even harder. If the saboteurs wanted to deal with

this further problem they could have became even more ambitious, they might wish

to block the supply lines for the import of sonar equipment; they might go to

the country of origin, or enlist local help, to prevent the manufacture of the

sonar. Eventually though, as this is the Culture of Maximum Harm, jealousy and

greed would take over, and the other crews would realise it was in their

immediate economic interests to install their own sonar systems, catch

everything they could, and to hell with the terminal decline of the fishing

stocks!

There are two lessons here. First,

the answer to a problem usually lies in a far more mundane place than people

realise; it is only the way that we have been manipulated that causes us to look

in the wrong places for solutions: to the law, to business, to politics, to

hope. We rarely look closer to home for answers. We rarely look in the mirror

and question our own motives. Richard Heinberg, author of Peak Everything has

this to say about our addled state:

As civilization has

provided more and more for us, it's made us more and more infantile, so that we

are less and less able to think for ourselves, less and less able to provide for

ourselves, and this makes us more like a herd – we develop more of a herd

mentality – where we take our cues from the people around us, the authority

figures around us.[iii]

Second, good intentions rarely last

long in this culture. In a way, there was some higher power in play here: the

power that makes people give up good intentions and follow the path chosen for

them by Industrial Civilization. The fishermen stopped trying to prevent the

problem getting worse and instead decided to put their own snouts into the

trough. That’s just the way it is: it’s what we have been brought up to do.

When you think about it, humans in

this culture seem to want conspiracy theories about strange things we

don’t understand; we seem to want unassailable forces running our lives from

ivory towers; we seem to want this because we cannot accept that perhaps we are

all in this together and the truth will hurt a bit too much. Driving a giant

SUV, flying half way across the world for pleasure or buying the results of

rainforest devastation because our culture makes these acts acceptable does not

absolve the user – we must take some responsibility, for without accepting our

role in this system then we have no chance of being freed from it.

You are part of the system. Get used

to it.

*

* *

The act of giving someone bad news is

often easier than the thought of doing so: the period leading up to giving this

news can get inside your head, invade your dreams and start to gnaw away at you;

the act of passing on the news might be uncomfortable, but the moment is quickly

gone, however difficult that moment is. The longer you leave things, the worse

it feels. Receiving bad news works in much the same way; except that usually

people don’t realise they are going to get it. The thought that something bad

might happen to you in the future; now, that really can play tricks with your

mind – you try and avoid the situation, put it off for as long as you can but,

as long as the outcome isn’t truly terrible, the execution is rarely as bad as

you imagine it might be.

In the movie “The Matrix”, the

thought that something was wrong gnawed at Neo, the perpetrator of eventual

change, for years; but when he found the truth, it was as much a liberation for

him as it was a shock. Neo found that he could do something about his situation

because he had knowledge, and because he fully understood his position. Once you

accept things as they are – that you are part of the problem and, thus, you

have a part to play in the solution – you actually start to feel better, as

though the weight of ages has been lifted from your shoulders.

You are part of the system; you have

to take responsibility for your part of the problem: how does that feel?

Your place in the system is as a

component in a massive food web. Like all food webs, it is driven by energy;

physical energy sources like oil, gas, coal and radioactive materials drive the

machines that ensure money keeps floating to the top of the vat where the Elites

skim it off to add to their wealth. If you are resourceful or in a role that

holds some status, you can have some of this wealth too, and the material

trappings that come with it. Without the energy that drives the web, though,

there is no money, and there is no web. It is not just the oil, gas, coal and

the various sources of radiation that keep the web operating though – people

are equally vital, more so in fact. Unless people run the machines, staff the

shops, build the products, drive the lorries, create the advertisements, read

the news and enforce the law, the web will collapse upon itself, bringing the

entire hierarchy down with it.

Think back to the chapter about cod.

The cod are positioned high up in the food web in terms of the amount of food

energy they require to remain alive: they operate at a high trophic level, but

without the organisms at the lower levels – the sand eels, the tiny copepods

and the minute plankton – they cannot exist. Without the cod, the scavenging

hagfish might start to suffer (although the windfall of bodies would provide

rich pickings for a long time) but the sand eels one level down would be

delighted: they would flourish. Think of your place in civilization; think of

your job, or your role in society, and how it relates to the people sitting

right at the top, or even those somewhere in the middle, aspiring to move

upwards. What do you want to be, a wheel or a cog?[iv]

Yes, you are part of the system; but

you are far more important than the people higher up in the web: you are the

engine, the energy source, the reason for its continuation. You are the

system. Without your cooperation, without your faith, the system would have no

energy and then it would cease to exist.

I don’t know about you, but that

makes me feel good.

Building

Solutions

Industrial Civilization has to end; I

made that clear in Part Three. There is no doubt that, sooner or later, it will

collapse, taking much of its subjected population with it: oil crisis, credit

crunch, environmental disaster, pandemic – whatever the reason, it will

eventually fail in a catastrophic manner. This may not happen for fifty or a

hundred years; by which time global environmental collapse will be inevitable.

That is one option; the other is for it to die, starting now, in such a way that

those who have the nerve and the nous to leave it behind can save themselves and

the natural environment that we are totally dependent upon.

Be assured, no one is going to go

into the heart of the “machine” and rip it limb from limb, because the

machine has no heart, it has no brain. This civilization is what we have ended

up with after a series of deliberate (and sometimes accidental) events intended

primarily to give power and wealth to a privileged few. What we have now got is

an entire culture that values economic growth above everything else, a toolkit

of malicious methods for keeping that cultural belief in place, and an elite,

ever-changing group of people who have become pathological megalomaniacs, unable

to cope with the sheer amount of wealth and power this culture allows them to

have.

Given that we all appear to be in

this together (although some of us are beginning to realise that it doesn’t

have to be that way) how on Earth is it possible to bring down something so

monumental? The answer lies in the nature of Industrial Civilization itself –

its key features are also its greatest weaknesses.

Take the simple article of faith that

is Economic Growth. We have, I guess, agreed that there is nothing sustainable

about it – however you cut the pie, the natural environment is bound to lose

out all the time the economy is growing. In order to sustain a “healthy”

level of economic growth, the consuming public has to know that when they spend

some money they will still have some left. The definition of “having money to

spare” has been stretched out of all proportion in recent years as creditors

have extended peoples ability to spend beyond their means, while still thinking

they are solvent. Whether that spare money is in the form of savings, cash,

investments or credit, though, the important factor is that the potential

consumer will stop being a potential consumer as soon as they realise there is

no more money left to spend. Having a paid job is one way of ensuring (at least

for a while) that you can pay for things; in fact, this is the major factor

affecting Consumer Confidence.

Across the world, governments and the

corporations that control them are in a constant cycle of measuring consumer

confidence. The USA Conference Board[v]

provides the model for most of the indices used by the analysts. The importance

of confidence to economies is critical:

In the most

simplistic terms, when…confidence is trending up, consumers spend money,

indicating a healthy economy. When confidence is trending down, consumers are

saving more than they are spending, indicating the economy is in trouble. The

idea is that the more confident people feel about the stability of their

incomes, the more likely they are to make purchases.[vi]

This creates an interesting

situation: it is possible, indeed probable, that to create catastrophic collapse

within an economy, and thus bring down a major pillar of Industrial

Civilization, the public merely have to lose confidence in the system.

This is reflected in other, related parts of civilization: following the attacks

on the World Trade Centers in 2001, the global air transport industry underwent

a mini-collapse; the BSE outbreak in the UK in the early 1990s caused not only a

temporary halt in the sale of UK beef, but also a significant drop in global

beef sales. Anything that can severely undermine confidence in a major part of

the global economy can thus undermine civilization.

The need for confidence is a psychological

feature of Industrial Civilization; there are also two physical features

that work together to create critical weaknesses. The first of these is the

complexity that so many systems now exhibit. I mentioned the “farm to fork”

concept in Chapter Eleven, indicating that the distance travelled by food items

is becoming increasingly unsustainable. Overall, the methods used to produce

food on a large scale, in particular the high energy cost involved in

cultivating land, feeding livestock, transforming raw materials into processed

foods, chilling and freezing food, retailing it and finally bringing it home to

cook, not only demonstrates huge inefficiencies but also exposes the number of

different stages, involved in such a complex system. The same applies to

electricity; in most cases electricity is generated by the burning or decay of a

non-renewable material, which has to be removed from the ground in the form of

an ore, processed and then transported in bulk to the generation facility. Once

the electricity is generated, in a facility with a capacity of anything up to

five gigawatts[vii],

it has to be distributed, initially over a series of very high voltage lines,

and then through a number of different power transformation stages (all the time

losing energy) until it reaches the place where the power is needed. Both of

these examples – and there are many more, including global money markets and

television broadcast systems – consist of a great many stages; most of which,

if they individually fail, can cause the entire system to collapse.

The second of this potentially

debilitating pair of features is the overdependence on hubs. Systems are usually

described as containing links and nodes, a node being the thing that joins one

or more links together; a road is a link, and the junctions that connect the

different roads together are the nodes. Systems that have many links and nodes

are called “networks”; food webs are networks, with the energy users being

the nodes, and the energy flows being the links. Networks made up of links that

develop over time, based on need, are referred to as “random” networks: the

US interstate highway system is one such random network, as is the set of

tunnels created by a family of rabbits. Networks created intentionally to fulfil

a planned purpose, usually with the potential to expand, are called

“scale-free” networks, good examples being the routes of major airlines.

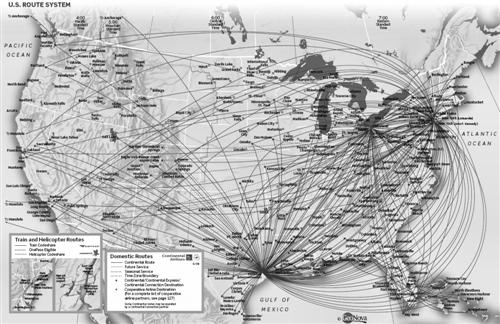

Figure

2: Route map for a major US airline, showing the almost total dependence on

three large hubs (Source: Continental Airlines Route Maps)

A node within a network that joins

together a great many links is known as a hub: Industrial Civilization uses hubs

a lot. Thomas Homer-Dixon describes the situation like this:

Although researchers

long assumed that most networks were like the interstate highway system, recent

study shows that a surprising number of the world’s networks – both natural

and human made – are more like the air traffic system. These scale-free

networks include most ecosystems, the World Wide Web, large electrical grids,

petroleum distribution systems, and modern food processing and supply networks.

If a scale-free network loses a hub, it can be disastrous, because many other

nodes depend on that hub.

Scale-free networks

are particularly vulnerable to intentional attack: if someone wants to wreck the

whole network, he simply needs to identify and destroy some of its hubs.[viii]

In July 2001, a railway tunnel fire

in Baltimore, USA caused the shutdown of a large part of the downtown area due

to the heat generated within the tunnel, and the health risk posed by an acid

spill. Over the next few days the surrounding rail networks were affected by the

extra freight traffic diverted onto other lines, causing a number of bottlenecks

in the greater Baltimore area.[ix]

There was also one unexpected impact: Internet access across much of the USA

slowed down dramatically. “The Howard Street Tunnel houses an Internet pipe

serving seven of the biggest US Internet Information Service Providers (ISPs),

which were identified as those ISPs experiencing backbone slowdowns.

The fire burned through the pipe and severed fiber optic cable used for

voice and data transmission, causing backbone slowdowns for ISPs such as

Metromedia Fiber Network, Inc., WorldCom, Inc., and PSINet, Inc.”[x]

The Howard Street tunnel was a major artery for Internet traffic; its severance

caused the same impact that the destruction of a major network hub would cause.

When you combine a set of key complex

systems consisting of a large number of interdependent components, with networks

that are increasingly becoming dependent on a small number of hubs, you create a

structure that is extremely sensitive; irrespective of any safeguards that may

have been built into it. Civilization is built upon these complex,

interdependent systems, and these systems rely on networks to keep the flows of

energy, data, money and materials moving. Civilization also depends upon its

human constituents (you and I) having complete confidence in the way it

operates: it needs faith. In both physical and psychological terms, Industrial

Civilization is extremely fragile: one big push and it will go.

*

* *

These are just thoughts, ideas,

imperfect sketches for something that could work if it’s done properly. I

can’t predict how things are going to turn out, even if what I am going to

propose does succeed; nobody can predict something that hasn’t started yet. My

train of thought won’t stop with the end of this book, but here’s where I am

at the moment:

1.

The world is changing rapidly and dangerously, and humans are the main

reason for this change. If we fail to allow the Earth’s physical systems to

return to their natural state then these systems will break down, taking

humanity with them.

2.

Humans are part of nature; we have developed in such a way that we think

we are more than just another organism; but in ecological terms we are

irrelevant.

3.

Regardless of our place in the tree of life, humans always have been, and

always will be the most important things to humanity. We are survival

machines.

4.

Our failure to connect the state of the planet with our own inarguable

need to survive will ensure our fate is sealed. This must not happen.

5.

In order to bring us to a state of awareness, we must learn how to

connect with the real world; the world we depend upon for our survival. We are

all capable of connecting.

6.

Our lack of connection with the real world is a condition that has been

created by the culture we live in. The various tools used to keep us

disconnected from the real world are what make Industrial Civilization the

destructive thing that it is.

7.

To gain the necessary motivation to free ourselves and act against

civilization we need to get angry; and use that anger in a constructive way.

8.

To understand how to remove Industrial Civilization we must realise that

we, along with everyone else in Industrial Civilization, are the system.

9.

Industrial Civilization is complex, faith-driven and extremely sensitive

to change and disruption. It will collapse on its own, but not in time to save

humanity.

I have read a lot of books, and a lot

more articles and essays related to the problems that we face. I have heard

people talking on the radio and on television proposing how everything can be

sorted out. I have seen some wonderful movies that describe where we are going,

how we got here and where we might be going. Some of these works reach an

ecstatic crescendo before petering out in a gentle rain of hope. Some of them

tell me what we should be doing; when it is obvious that the things suggested

will not help, and could even make things worse. Some of them tell me I should

not be looking for “solutions” to the problem at all – that there are no

solutions, no cures, probably no chance at all. I haven’t read, heard or

watched anything that could actually make things better.

Have I missed something?

I don’t think so. For one thing, I

don’t subscribe to the idea that there are no solutions: agreed, there is no

way of knowing if I have left something out – I probably have – and no way

of completely tidying up the fallout that will inevitably result from the

massive shift in society that is required. But that doesn’t mean you can’t

have solutions, providing you know what the problem is. I know what the problem

is, and so do you: at its heart, it is not environmental change and it is not

humanity itself – it is that we are disconnected from what it means to be

human. The solution is the answer to this simple question:

How can we reconnect with the real

world?

I’m not asking people to help build

a new set of systems, construct a new world order, design a new future – that

kind of ambition is the stuff of civilization; the stuff of control, hierarchy

and power. Connection is the most liberating, and powerful step you can take. If

you know what is happening; if you know why it matters; if you know how to

connect; and if you have the strength to reject the way this culture disconnects

us, then you can change your own world, at the very least. That is the start of

everything.

There are two dimensions to the

solution, both of which I want to briefly explain before I show you the

solution. The reason I am using dimensions is because the solution is not

simple; it is much easier to understand something complex if you can break it

down a bit.

The First Dimension: Cutting

Across

In this dimension are the different

actions that can be carried out to deal with the problem itself: our lack of

connection. There are a few different aspects to this, some of which are more

useful than others; but the nature of them makes it difficult to just make lists

– they do tend to cut across each other depending on how you approach the

problem. For instance, if we assume (correctly) that to bring civilization to

its knees, economic growth has to stop, then it would seem logical to directly

attack the instruments of the global economy: the investment banks, clearing

houses, treasuries and the various things that link these nodes together. The

problem is that, however exciting an idea this is, it doesn’t deal with the

deeper problem – that civilization actually wants economic growth to take

place: unless this mindset is removed then the systems will just be rebuilt in

order to re-establish a growing economy.

Even more fundamentally, unless the

reasons people feel that economic growth is necessary, i.e. the Tools of

Disconnection are removed, then very few people are likely to spontaneously

reconnect with the real world and reject economic growth. You can see, straight

away, why a number of different dimensions are necessary. To put it simply,

though, the “cutting across” dimension consists of those actions that (a)

remove the forces that stop us connecting, (b) help people to reconnect and (c)

ensure that the Tools of Disconnection cannot be re-established. If you are

keen, try and think of at least one way to address each of these; then see if

ours match up later.

The Second Dimension: Drilling

Down

Almost every “solution” I have come

across only deals with the problem at one or, at most, two levels. I feel like a

razor blade company now, by saying I have a three level solution (“Not one,

not two, but three levels of problem solving!”) but it’s no accident there

are three levels. I started thinking about the nature of the problem at a fairly

superficial level – the kind of level most of the “one million ways to green

your world” lists pitch at – and immediately realised that, while suggesting

what can be done to make things better is necessary, it assumes that there is a

huge mass of people who actually want to do these things. You know

already that very few people are connected enough to go ahead and do the, quite

frankly, very radical things that need to be done: two more levels are

necessary.

The second level, therefore, looks at

the way individuals and groups of people change over time, and how the necessary

changes in attitude can be transmitted throughout the population in a structured

way, then accelerated beyond what conventional theory tells us is possible. I am

only going to touch on the theory of this as it is pretty dry stuff, but the

practical side of it makes for very interesting reading. The beautiful thing

about using this multi-level approach – which you may already have realised

– is that activities can be taking place at the first level, amongst the

people who are already connected and ready to act, which then makes the process

of motivating the more stubborn sectors of the population progressively easier.

References

[i] That’s “green” consumption. A marvellous misnomer that I would use far more if anyone understood what it meant.

[ii] For examples you can visit www.conspiracyarchive.com, www.conspiracyplanet.com, www.theforbiddenknowledge.com and www.abovetopsecret.com. There are lots more you can try. The sad thing is that there are a lot of clever people writing a lot of good stuff, but conspiracy theories keep sidetracking them. Remember, a conspiracy is simply groups or individuals working together out of the public eye: you only have to read Chapter Thirteen to realise that the really sinister operations of Industrial Civilization are widely known; but we ignore them because “that’s the way it has to be”.

[iii] Quoted in “What A Way To Go: Life At The End Of Empire”, 2007, Directed by Tim Bennett, www.whatawaytogomovie.com.

[iv] Dmitry Orlov, “Civilization Sabotages Itself”, http://www.culturechange.org/cms/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=111&Itemid=42 (accessed 7 May, 2008)

[v] As of April 2008, the US Consumer Confidence Index was down, reflecting the dicey position of the global economy: a combination of the “sub-prime” market collapse, and the huge rise in oil prices. http://www.conference-board.org/economics/ConsumerConfidence.cfm (accessed 7 May, 2008).

[vi] Jim McWhinney, “Understanding the Consumer Confidence Index”, Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/articles/05/010604.asp (accessed 7 May, 2008).

[vii] Derived from MWh figure for global generating stations at http://carma.org/plant (accessed 8 May, 2008).

[viii] Thomas Homer-Dixon, “The Upside Of Down”, Souvenir Press, 2007.

[ix] Mark R. Carter et al, “Effects of Catastrophic events on Transportation System Management and Operations: Howard Street Tunnel Fire.” US Department of Transportation, 2001.

[x] Ibid.