|

Chapter

16

Making

The Change

Where do we need to end up? I suppose

the best answer I can give you at this stage is, humanity in a state of

connection with the world around it, living with a dramatically reduced impact

such that the Earth’s natural systems can once again function normally – any

further and things start to get much more difficult to predict. In many ways

that simple, non-prescriptive statement is exactly how it should be. My decision

not to offer you a fully mapped out, single new way of living, beyond the

wonderful state of being connected was inspired by Daniel Quinn:

There is a clear

sense in which ours is just a special case of a much wider story, written in the

living community itself from the beginning, some five billion years ago: There

is no one right way for ANYTHING to live.

This is how we humans

got from there to here, by enacting this story, and it worked sensationally well

until about ten thousand years ago, when one very odd culture sprang into

being obsessed with the notion that there must be a single right way for people

to live – and indeed a single right way to do almost everything.[i]

You realise now that our disconnected

state is the outcome of this sprawling homogenous system that has one aim: to

have more of everything. The way the vast majority of us are living has been

decided for us by the culture that we live in, of which we are an intrinsic

part. Because they are only present in civilizations, neither governments nor

corporations have any part to play in the solution. Despite the

protestations of the mainstream environmental movement, it is obvious now that

the best thing corporations and governments can do is to shut up shop and leave

humans to go back to the emphatically less destructive beings they were before

Industrial Civilization took control. My job is in all of this is to get us to a

point where we can make the decision to change for ourselves – with a clear,

open, connected mind; unfettered by blind ambition; uncontaminated by

civilization.

Level One: Ways To Live

Given that this book’s aim is to

regain our lost connections with the real world, and given what I have said

about the superficial nature of “green” lists, it might seem odd that I am

now going to describe some key “greening” actions: actions that will

dramatically reduce our impact on the natural environment. The reason for this

is that I believe the best actions are those with multiple impacts – the

direct impact of the actions I am going to propose is, indeed, to reduce the

amount of greenhouse gases being emitted by human activity, reduce the amount of

ecological degradation taking place, and to allow the Earth’s natural

biological and chemical processes to begin to return to a stable state. The very

welcome side effect of these actions is they trigger the rapid reversal of the

industrial or capital-based economy.[ii]

Just as the success of Industrial Civilization is defined in terms of economic

growth, a lack of economic growth will cause Industrial Civilization to break

down[iii]:

Modern capitalism’s

stability – and increasingly the global economy’s stability – requires the

cultivation of material discontent, endlessly rising personal consumption, and

the steady economic growth this consumption generates.[iv]

The author of this statement goes on

to insist that a failure to grow will result in rapid and fierce societal

breakdown: a “zero-sum conflict” (i.e. a battle to gain the most of a finite

resource). To a person rooted in the Culture of Maximum Harm, that sounds like a

good reason to maintain economic growth forever; to ensure there is always

enough to go round to satisfy an insatiable desire for more of everything. To me

this sounds like a system that is fatally flawed and needs to be removed from

the face of the Earth, before the inevitable ecological collapse brings it down

in far more horrible circumstances. Whether you agree with this thesis depends

on whether you place any value on having a liberated, connected and survivable

future.

There is a third role that these

actions fulfil, and that is of engaging individuals with their actions; in other

words, allowing people to think about the impact – both positive and negative

– of the things they do. As an example, simply by localising your food supply,

you have to understand the processes by which your food gets to you, and thus

you become engaged. Even deciding not to do something (by which I mean, making a

conscious decision to reject a suggestion), you still have to engage your

thought processes in the issues. Not surprisingly, this works at many levels,

particularly Level Three: Influencing, which we will come to later on.

The following list is not exhaustive,

but based on my own work, and that of countless other writers, scientists and

thinkers; they are the things, which I believe to be potentially most effective

in fulfilling the joint purpose set out above. The quicker and more thoroughly

the suggestions are followed, the more rapid the impact will be. I have

intentionally left out the act of Connecting from this list as it is implicit in

everything that humans do in their lives – if you need a reminder on the

reasons for connecting and how to do it, please read Chapters Eleven and Twelve.

Finally, there is one more item, near the end of the list which may not seem

to fit in with the rest – the act of sabotage – but in leaving it out I

would be ignoring an essential tool in the armoury of anyone serious about

reclaiming their liberty: it is as much a constructive action as all of the rest

I have listed.

Consuming

There are commonly thought to be three

R’s in environmental parlance: reduce, reuse and recycle. Except, very few

people in this culture bother doing the first two because we have been led to

believe that doing the last one is enough – which would be funny if it

weren’t so serious. It’s time to add a couple more R’s to the list, and

get rid of one: here are my four:

Reduce: Do I need to buy this

thing at all?

Repair: Can I repair or refurbish

this thing, or have somebody do it for me?

Reuse: Can I buy or obtain this

thing, or something similar, pre-owned?

Respect: Can I look after this

thing better?

To take the simple act of reducing:

if every person in Industrial Civilization were to reduce their consumption of

all goods and services by 25 percent, this would cause a contraction in the size

of the economy (in fact, even if everyone just bought the same amount of stuff

each year the economy would start to sputter!) sufficient to cause serious

problems for speculators and governments alike. If you focus that overall

reduction on non-essentials – such as consumer electronics, leisure goods and

services, and cosmetic home improvements – then those parts of the economy

will fall apart rapidly. It is those parts of the industrial economy that

maintain overall economic growth, because they take up the slack left by the

“essential”[v]

economy (staple food, healthcare, utilities, education etc.) that, because of

its non-consumer nature, grows very little or not at all. Giving up a new TV or

a cinema trip won’t do anything to save the world, but it will curtail overall

economic growth and also hit advertising and promotional (i.e. tools of

disconnection) budgets. That said, reducing your consumption of “essential”

items, such as energy, also has an obvious environmental benefit, and again

helps to move the economy in the right direction. It is vital to remember that we

are not consumers; we are individuals who may or may not choose to buy

things – individuals who cannot be pigeonholed into convenient categories for

the benefit of the economy.

Repairing, which includes

refurbishing and renewing parts of the things that you already have, makes the

act of reducing the purchase of new things far easier. Of course, Industrial

Civilization will try and convince you that you need to upgrade that thing

because having the latest thing is part of living the consumer dream: but there

is more to repairing than just keeping the same thing functional – it also

brings a sense of pride and ownership. A chair with a broken leg is, in the eyes

of the consumer culture, crying out to be replaced with a new chair – hell! Go

and by a whole set of them! But if you insert a small piece of dowel, and then

glue or screw the leg back in place, you now have a chair that you repaired.

How could you just throw it away now? Repairing and building from scratch –

things we have clearly forgotten how to do, by virtue of the off-the-shelf

economy – are ways of connecting with the belongings you have: they allow you

to Respect what you have. Once you start to respect the things you have, then

you don’t want to throw them away – and you treat them with care.

Manufacturers may give goods “planned obsolescence”, so that they stop

working after a short time, but you can extend the lifetime of something

indefinitely if you look after it.

Then there is the important act of

Reusing. Logging onto eBay, or going to the charity shop is certainly one way of

reusing pre-owned goods – again, this results in the reduction of goods that

are bought new, causing the economy to contract – but these activities can be

brought closer to home by selling things directly that you no longer need, or

just giving them away. Two simple activities are almost absent from the

money-based lives we now lead: donation and bartering. Donation is just giving

something away – don’t want that table that has been cluttering up the shed,

just give it to someone; want a bicycle but don’t even have a broken one to

repair – go and see what other people have thrown out in their skip or

dumpster. Donation can work both ways. Barter, on the other hand, always works

in two, or more ways: if you have a service you can offer, or something you have

made or grown, then exchange it for something someone else has. I may have a

glut of tomatoes this summer from my garden, and someone up the road has some

seasoned firewood I could use in my burner – guess what I’m thinking.

Donation and barter are invisible

activities as far as Industrial Civilization is concerned, because they have no

economic value; but they are perfect as tools for beginning a new way of life

that doesn’t require the exchange of cash, or the needless production of

goods. One measure of how threatened a civilization is, is the laws it makes:

George Bush Jr. and his economic advisors may have found it prudent in 2008 to

bribe middle and high-income earners to spend more money on consumer goods[vi],

but the moment certain activities start to threaten the industrial economy you

can be sure they will be made illegal. I am not allowed to remove unbroken

plates or perfectly good books from the dumpsters at my local recycling site:

this is nothing to do with liability; it is everything to do with threatening

economic growth.

In all cases where an activity has a

negative impact on the natural environment, and hence human survival, the act

of reducing must always be the first option in the decision making process.

Eating

There are three facets to eating that

should all be taken into account: how much you eat, what you eat, and how it is

produced. It would be easy to fill an entire book with analysis on this very

emotive subject – emotive because what you put in your body, in a very real

sense, defines what you are – but a few words on each should be sufficient to

make things clear. First, how much you eat goes back to the last section on

consuming. Obviously the less you eat, the less energy, soil, chemicals and

labour is required to produce it; but there is clearly a minimum amount of food

that can be healthily consumed depending on what kind of life you lead –

it’s about 2500 kilocalories for a man, and 2000 for a woman. If you are

eating more food than you need then reducing it will go some way to reducing

your impact, but not very far.

Obesity is a major health issue for

societies not just in highly Westernised areas, but also in those areas just

beginning to be touched by the aggressive hand of commercialism: why eat a

sandwich when you can have a Big Mac; why have a glass of water when you can

have a Coke? Overweight and obese people, surprisingly, aren’t eating more

calories than those people of a healthy weight – they may even be eating

fewer, as those with very physical lives have to consume more to stay healthy

– but they are eating more calories contained in fats[vii]

and processed sugars. Obesity is a symptom of the lifestyle that most benefits

the consumer culture: sedentary, digital and mechanised living; a diet dominated

by processed, high profit foods. What you eat, the second facet is very

important here.

As I showed earlier, unless you are

self-sufficient, a diet containing a high volume of meat is environmentally

unsustainable; so the first, and simplest way of reducing the environmental

impact of a diet is to reduce the amount of meat contained in it. As I also

alluded to in Chapter Fourteen, a diet dominated by meat or processed foods

requires far more stages of production than a diet which is based around things

that come straight out of the ground and into your mouth. Obviously some element

of processing is required for many foods, but the fewer stages that are

required, the lower the environmental impact of that food, and the less the user

of that food depends upon the industrial food processing system.

This takes us neatly into the third

facet: how your food is produced. Recently, I have started saying to people that

there are three skills that every person will have to have in order to survive

the future (whether it changes by accident or design): the ability to make

simple things, including structures, from scratch; the ability to cook good,

nutritious meals from basic ingredients; and the ability to grow, and rear if

necessary, your own food. Step back only a few decades and it would have been

unthinkable to not be able to do these things, yet it seems that part of the

disconnection that civilization has forced upon us is to make us lose these

critical life skills. We have become dependent upon the various systems of

this culture to provide us with what we, until recently, could provide for

ourselves: right down to the insipid, packaged ready-meals that masquerade

as food.

Since giving up paid work as part of

the industrial economy a year ago – making myself no longer “economically

viable” – I have learnt to repair and make lots of things from scratch; cook

a huge variety of meals with whatever food is local, in season and from my store

cupboard; and, starting with herbs and leafy vegetables, have gradually learnt

how to grow my own food. Taken together, these three things have made me feel

extraordinarily liberated and given me the confidence to do more. Not

surprisingly, I have also become connected with the things I have made, the food

I use, and the small patch of earth that will be providing my family with more

and more good stuff as time goes on.

I wonder how long it will be before

growing food in back yards is made illegal.

Travelling

There are two major types of transport:

motorised and non-motorised. They are easy to distinguish, especially in the

eyes of a child who hasn’t yet been indoctrinated in the ways of the machine:

cars, trucks, trains, aeroplanes, mechanised boats, motorcycles and coaches are

all motorised; legs, bicycles, sailboats and animal-drawn vehicles are not

motorised. Deciding between a mode of transport that is very energy efficient

(non-motorised) and one that is not (motorised) is simple, really; although you

would be forgiven for thinking it is not. You see, manufacturers, and all of the

other vested interests involved in a particular mode of transport – especially

the money-rich car and air industries – will do anything to ensure you stick

to that mode of transport. Aircraft manufacturers make a big deal of the energy

saving potential of the new Airbus-A380 or Boeing 787, whilst conveniently

glossing over the need to burn tonnes of fuel to keep an enormous lump of metal

in the air. Car manufacturers (along with their good friends in the oil

industry) bring out all sorts of new “green” vehicles, whilst at the same

time fighting to ensure that fuel economy regulations are kept strictly

voluntary.[viii]

Changing the way we travel is about far more than changing the model of vehicle

or the airline we use – these are blatant distractions from the real issue –

it is about the method of transportation we use, and the distance and rate by

which we travel in the first place.

In essence, the method we use to get

around is far more important than distinguishing between different versions of

the same method. Some recent work concluded that the humble bicycle was the most

efficient (land based) form of transport by a long way[ix],

which makes perfect sense when you consider the combination of gear system,

efficient traction wheels and most importantly, being powered by a human being,

rather than a combustion or electrical engine. Human beings produce only 100g of

CO2 in their breath cycling or walking twenty kilometres, compared to

a car producing between three and six kilograms of carbon dioxide.[x]

However, this kind of exertion would require about 500 kilocalories, which if

taken in the form of beef would emit around seven kilograms of carbon dioxide.[xi]

This latter information has, not surprisingly, been used as a reason to drive

rather than walk[xii]

– assuming people eat nothing but beef. If you have an average global diet,

though, with only 15 percent of your calories from meat, then the total carbon

dioxide emissions of human and bicycle (or on foot) are well under a kilogram.

The point of this analysis is not

only to debunk some of the more fatuous arguments put forward by transport

industry lobbyists, but also to show how obvious it is – by using a little bit

of common sense – that motorised transport is not the way forwards, regardless

how “green” a manufacturer may claim their vehicle is. Bear in mind, also,

that a vegan (based on discussions in Part One) would emit less than half a

kilogram of carbon dioxide all-in over that twenty kilometres: far better than a

fully laden bus or coach. Self-propelled, non-motorised transport is a threat to

civilization; which is the perfect reason to switch the engine off for good:

The cyclist creates

everything from almost nothing, becoming the most energy-efficient of all moving

animals and machines and, as such, has a disingenuous ability to challenge the

entire value system of a society. Cyclists don't consume enough. The bicycle may

be too cheap, too available, too healthy, too independent and too equitable for

its own good. In an age of excess it is minimal and has the subversive potential

to make people happy in an economy fuelled by consumer discontent.[xiii]

More important even than method,

though, is distance and speed. Culturally, the world is getting faster, not only

in terms of transportation but also the accelerating flow of information

intended to keep us consuming, and keep us disconnected from the real world. The

automobile made door-to-door rapid transportation possible, as well as being

responsible for a large proportion of the anthropogenic greenhouse effect. In

every industrial nation, the car is king, with the aeroplane coming up a close

second – able to take people further and more quickly than any other form of

mass transport. The “need for speed” is a symptom of our perceived lack of

time: no longer is the journey part of the experience; it is merely an adjunct

to the destination we must reach. The relationship between speed and distance is

two-way, with great distances being achievable due to the great speeds we can

attain, and great speeds being “necessary” due to the great distances we

wish to travel. Neither the desire for speed, nor the desire for distance is

natural – Industrial Civilization, wishing to squeeze more and more profit out

of synthetic desires, has placed them in our minds. The reason speed creates a

thrill is because humans are, rightly, afraid of its potential to injure or kill

– yet travelling faster than our legs can carry us is considered a positive

thing, largely because there is money to be made out of it. The reason we desire

to travel long distances is because the travel industry tells us we should.

About fifteen or sixteen years ago I

made the decision to travel only within my own country: not for any jingoistic

reason, but simply because I realised that there was so much to discover and

enjoy close to home – I didn’t need anywhere else. Around the same time as

making this decision, and perhaps they were related, I completed a transport

study of the road network on the small island of Guernsey. What I discovered was

that, before 1800 (around the time when roads were built to protect against

Napoleonic invasion) the vast majority of travel took place within individual

parishes, little more than a couple of miles across: a holiday was a week in a

neighbouring parish. Travel took place from home to the market, to friends and

family, to places of worship and to places of work – all of which were within

easy walking distance.

The logical response to the immense

pressure on us to travel further, faster and by more technically complex forms

of transport is to draw back; to only travel where and in a way that you

consider absolutely essential, not that which has been decided by civilization

on your behalf. This is the way humanity was until very recently: having what

we needed close to us (like food, family and friends), learning what the

local environment had to offer and making the best of it. It may not be possible

where you are to live in such a way, but then perhaps that is the best reason of

all to step outside of the system and make your own decisions.

Living

Everyone needs a place to call home, but

not every place people call home is a place desirable to live in. Without clean

water, clean air and an appropriate level of shelter and warmth, no one can

reasonably be expected to live for long: yet across the world, the civilized

world of cities, industry and democratic governments; people live in conditions

that an Inuit, an Apache, a !Kung or a Taíno would never call “home”. Those

at the bottom live in conditions of grinding poverty, kept afloat by the crumbs

of the industrial economy and the daily promises of material fulfilment. Those

at the bottom of civilization are far worse off for the real needs of humans

than most of those who lived (and still live) “uncivilized” lives.

Those above the breadline, living in Industrial Civilization,

have the basic necessities of a fulfilled life: then they are exhorted to pack

these lives out with excess as soon as a bit more money becomes available. The

excess – the entertainment system, the air conditioning, the conservatory, the

fully-fitted kitchen – provides some superficial pleasure, while at the same

time driving a wedge between individuals, their families, their communities and

nature. The plastic bubble of modern living provides the perfect cultural

prophylactic: a barrier between you and the real world.

Is there no middle ground?

In this culture, I don’t believe

there is, unless somehow you are able to distance yourself from every attempt to

disconnect you. There reaches a point, though, when you can go no further: you

cannot go beyond civilization if you exist within civilization[xiv].

When I suggest a raft of different means for reversing the damage and

disconnection caused by our consuming, our eating and our travelling, I know

that at some point we are all going to have to say, “I would love to, but I

can’t, because the system doesn’t allow it.” That is the point at which

you need to step outside of the system, and go beyond civilization.

If you consider the home; the typical

brick, wood or concrete built home of a Western civilian, with space and water

heating, running water and sewerage, lighting and various electrical appliances,

certainly there are huge steps that can be made in order to reduce its

environmental impact. There are huge steps that can be taken to reduce the

dependency of that home, and that of the people living in it, on the

infrastructure laid down by the various profit-making utilities – some of

which are even recommended by authorities and suppliers. Most of these run off

the tongue of the average Westernised civilian: turn your heating and your air

conditioning down; switch off lights and appliances; buy energy efficient

devices; have showers instead of baths; install double glazing and loft

insulation. There are options for going a bit further, too: you can install

solar heating and electricity; you can install a wood burner for space heating,

and also use it to heat water; you can install ground or air-sourced heat pumps,

wind turbines, combined heat and power; you can plant cooling greenery, louvres

and shutters, passive solar capture systems. Use some common sense, and you can

make quite a big difference.

But there is a catch: governments and

utility companies assume that most people won’t do these things so the overall

impact of these actions is minimal; as soon as the majority of people start

doing these things, the energy companies start to cry foul – the grants dry up

and the exhortations mysteriously stop. This suggests that, as with consuming,

eating and travelling, a large number of people changing the impact of their

daily lives will start to hurt the economy; and that is why governments,

utilities and the environmental organisations that follow their lead, stop short

of asking for major societal change in the way that people live within

Industrial Civilization. It is not in their interests for things to change too

much – in fact it would be commercial suicide.

Just how easy is it to really take

yourself “off grid”? At what point do you decide that you don’t need mains

water or sewage? When exactly do you ask the local authorities to stop

collecting your trash? Just about the point at which your use of energy and

water, and your production of waste, have dropped to less than the level of a

“civilized” person. That’s the point at which you probably start

experiencing freedom.

Working

At what age do you think your working

future is planned out for you? I think by now you wouldn’t be surprised that

the answer is: “from birth”. There is a separate section in this chapter

called Educating, but it’s nothing to do with the education system and it is

nothing to do with on the job learning or career paths; after all, working is

what people have been brought up to do in Industrial Civilization, and not just

any old work. If you cast your mind back to Chapter Eight, where we thought

about population, you will remember that it was the Industrial Revolution that

was largely responsible for the beginning of the population explosion: a mass of

willing slaves brought up in the cities to be components of the industrial

machine. To create wealth you need product; to create product you need people.

There were a few who saw what was

going on and realised that some of the most brutal aspects of physical work

needed changing: the great philanthropists of the West – Titus Salt, Lord

Leverhulme, Joseph Rowntree – bear the passing of time, mellowed into a

whimsical tale of pure goodness; ignoring the fact that the philanthropists were

largely ensuring that their workforces remained loyal and hard-working. To be

blunt, working during the Industrial Revolution in the West was hell; working in

the new Industrial Revolution in the sweatshops, mines and factories of China,

India, Indonesia, Vietnam…different sets of eyes, but the same vision of hell.

Time may have passed, but all that has really changed is the location.

Yet, incredibly, the participants see

such conditions as a necessary evil. Unionisation, a living wage and the promise

that the company will do its best not to shorten your life is the best that can

be hoped for. Such “victories” make life tolerable for those people working

to make the shoes you wear, the food you eat and the televisions you watch, but

they do not change the fact that we are all part of the machine. The education

system is where it starts.

For centuries governments and

dictators have twisted a population’s knowledge base to their own ends. We may

look back in history, and gape at the ritual burning or enforced suppression of

the works of authors whose printed ideas did not match those of the accepted

orthodoxy, but the flames are closer than we like to admit. The Nazi elite

stirred up hatred of anti-Nazi materials in a coordinated “synchronization of

culture”[xv],

while only a decade later the US government elite stirred up hatred of

left-leaning beliefs in a coordinated exhumation of so-called Communist

sympathisers; the Chinese government installed the Great Chinese Firewall to

suppress “immoral” Internet access, while at the same time the US government

continue to control information coming out of wartime Iraq and Afghanistan

through the use of “embedded journalists”. In the last few decades, stories

of censored schoolbooks in far off lands[xvi]

have made those in supposedly more enlightened nations cringe, yet in a culture

that apparently promotes freedom of thought and expression, teachers are forced

to become mouthpieces for the Culture of Maximum Harm:

The Government has

worked with partners from the statutory and voluntary and community sectors to

define what the five outcomes mean. We have identified 25 specific aims for

children and young people and the support needed from parents, carers and

families in order to achieve those aims…[xvii]

This is from the

UK Government Every Child Matters programme, which “sets out the national

framework for local change programmes to build services around the needs of

children and young people so that we maximise opportunity and minimise risk.”[xviii]

Twenty-five aims, supposedly to promote the well-being of children, yet

containing the following items:

·

Ready for school

·

Attend and enjoy school

·

Achieve stretching national educational standards at primary

school

·

Achieve stretching national educational standards at secondary

school

·

Develop enterprising behaviour

·

Engage in further education, employment or training on leaving

school

·

Ready for employment

·

Access to transport and material goods

·

Parents, carers and families are supported to be economically

active

National educational standards;

Enterprising behaviour; Ready for employment; Access to…material goods;

Economically active – the progression is there for everyone to see. Even when

veiled as being in order to “improve the lives of children”, the educational

system is little more than an instruction manual for creating little wheels and

cogs. I urge you to look at your own national curriculum, searching for words

like Citizenship, Enterprise and Skills – it won’t take long to find the

real motivation behind the education system where you live. “A child in the

work culture is asked, ‘What do you want to be?’ rather than ‘What do you

want to do?’ or ‘Where do you want to go?’ The brainwashing to become some

kind of worker starts young and never stops.”[xix]

This is a wake up call: look at the

work you do and how it neatly fits into the industrial machine, ensuring

economic growth and continued global degradation; think about your job and what

part it plays in ensuring we remain disconnected from the real world; read your

children’s books, talk to their teachers – find out how your own flesh and

blood is being shaped into a machine part. As we are encouraged to work more and

more in order to feed our inherited desire for material wealth and artificial

realities, we lose touch with the real world; we pack our children off to day

centres and child minders in order that we can remain economic units, and stop

being parents; most of us work to produce things that nobody needs, and we are

unable to perceive the things that we do need – food, shelter, clean air,

clean water, love, friendship, connection.

The vast majority of us don’t need

to do the job we do. The lucky few, who through chance or design have found work

that is a fulfilling part of their lives rather than their lives being a slave

to work, provide examples for the rest of us. Once you decide to break out of

this cycle for all the right reasons and reduce your expenses to the bare

minimum by refusing to follow the instructions of civilization, leaving your job

and taking on something that provides you with a real living becomes easy.

Reproducing

I’m rarely afraid of stating the

truth, but some truths are far harder to give than others; one of them is that

people will die in huge numbers when civilization collapses. Step outside of

civilization and you stand a pretty good chance of surviving the inevitable;

stay inside and when the crash happens there may be nothing at all you can do to

save yourself. The speed and intensity of the crash will depend an awful lot on

the number of people who are caught up in it: greater numbers of people have

more structural needs – such as food production, power generation and

healthcare – which need to be provided by the collapsing civilization; greater

numbers of people create more social tension and more opportunity for extremism

and violence; greater numbers of people create more sewage, more waste, more

bodies – all of which cause further illness and death.

Civilization is defined, more than

anything else, by the cities in which it primarily operates: as the cities get

larger, they must import more and more energy, food, materials and finished

goods from a larger area outside of the city; and they must also become more

complex. You cannot simply make systems bigger to support larger numbers of

people; above a certain threshold a “step change” is required, and a layer

of complexity has to be added – such as requiring a distribution system to

feed a million people, compared to a single farmer who can directly feed a few

dozen people. This leads to considerable stresses. As Joseph Tainter writes:

More complex

societies are more costly to maintain than simpler ones, requiring greater

support levels per capita. As societies increase in complexity, more networks

are created among individuals, more hierarchical controls are created to

regulate these networks, more information is processed, there is more

centralization of information flow, there is increasing need to support

specialists not directly involved in resource production, and the like. All this

complexity is dependent upon energy flow at a scale vastly greater than that

characterizing small groups of self-sufficient foragers or agriculturalists.[xx]

The city progressively becomes a helpless foetus feeding

through the city’s umbilical linkages with itself and – particularly the

energy gleaned from – the outside world. If those links are severed, or the

multi-level systems that civilization depends upon start to break down, then the

city becomes helpless: it starves to death. The more complex and dependent the

systems required to support the larger number of people are – the more rapid

and more intense the crash is likely to be. More fundamentally; the larger the

city, the larger the mass of people in one dependent location and thus, the more

people will be killed in one go by a catastrophic systemic failure. As

Industrial Civilization becomes more urbanised, passing fifty percent of the

global population and ninety percent of the population of many highly

industrialised nations[xxi],

the risk of catastrophic collapse continues to intensify.

In short, the greatest immediate risk

to the population living in the conditions created by Industrial Civilization is

the population itself. Civilization has created the perfect conditions for a

terrible tragedy on the kind of scale never seen before in the history of

humanity. That is one reason for there to be fewer people, providing you are

planning on staying within civilization – I really wouldn’t recommend it,

though.

The second reason is slightly more

obvious and has been covered earlier in this book: the more people there are,

the more resources they will use up, the more greenhouse gases they will release

and the more damage they will do, as more people become consumers within the

Culture of Maximum Harm. The plan, after all, is for every human on planet Earth

to become a good consumer. Reducing the population in an increasingly resource

hungry society is essential to prevent a net increase in environmental

degradation. Even if you are planning to leave civilization it’s not the kind

of thing you can rush into, and the vast majority of people walking the road

from hell are going to spend a few years on that road. You will remain a de

facto civilian until you leave and, within the system, are bound to create

more waste, emissions and degradation than outside of it: Industrial

Civilization makes a virtue of excess. Morally, fewer offspring is something you

have to seriously consider until you are no longer dependent upon civilization.

A third, and rather more proactive

reason to have fewer children, is to hasten the shut down of the industrial

machine. This seems a little contradictory, considering that fewer children will

reduce the intensity of societal collapse, but there is a big difference between

wanting to bring down civilization in a measured way (well, as measured as we

can manage, given its complexity), and wanting to ensure that millions of people

die in a catastrophic implosion. I may be pragmatic, but I’m not that pragmatic!

The key point here is that civilization needs people to keep it going: as I made

clear in the last section, humans are the feedstock of the industrial machine.

The fewer people there are, the fewer empty, consumer-driven “opportunities”

can be filled. Of course, commerce being what it is, the desire for production

will move from an area bereft of willing slaves to one where the population has

been suitably primed to leap on the new positions being created – apparently

for their benefit. But that is ignoring the fact that Western economies in

particular, at least on a national scale, really do suffer when there is a drop

in the availability of suitable local workers.[xxii]

Not having children could be a very useful strategy, both for destabilising an

economy, and removing the worries of bringing up children in a collapsing

society.

There is a fourth reason, but it is

nothing to do with living within civilization. Later on you will learn why

balancing the number of children you have with the need to keep humanity going

will be critical in ensuring you can thrive in a world outside of civilization.

Let’s not go there for the moment – there is vital work to be done now.

Restoring

The Earth’s natural systems will, over

time, do a wonderful job of restoring the planet to a stable condition –

providing civilization has gone. In the presence of Industrial Civilization,

these systems are struggling to overturn the changes that our culture is heaping

upon the planet. The increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases exceeds any

previous increase in speed and intensity; the removal of forests and other

critical ecosystems is – in any normal sense of the word – irreversible

through natural processes; rivers, seas and groundwater are being toxified not

only by excessive quantities of basic elements and natural molecules, but also

by large amounts of synthetic chemicals for which there are no natural

restorative processes. Civilization has placed a burden on the Earth that – if

we are to survive beyond the next one hundred years – will have to be peeled

back by humans.

There are two ways to do this: the

first is a combination of Unloading and Setting Aside; the second is Active

Restoration. Within the Culture of Maximum Harm the first option is impossible

to achieve.

Unloading essentially means the

removal of an existing burden: for instance, removing grazing domesticated

animals, razing cities to the ground, blowing up dams and switching off the

greenhouse gas emissions machine. The process of ecological unloading is an

accumulation of many of the things I have already explained in this chapter,

along with an (almost certainly necessary) element of sabotage. If carried out

willingly and on a sufficiently large scale, this process would require

dismantling many of the key components of civilization; no person would be

foolish enough to cut off their own limbs unless they were suffering from some

kind of psychotic delusion, and no civilization would be willing to remove many

of the pillars of its own existence. Looking from the outside, though, a

civilization hacking off its own extremities would seem like exactly the right

thing to do. It’s not going to happen, of course.

Setting Aside is similarly suicidal

for civilization. In order to continue the upward spiral of economic

development, acquiring all of the symbols and cultural attitudes that entails,

an increasing amount of resources have to be used by civilization. For example,

in order to support an increasing desire for a civilized diet containing fish,

the oceans have to be stripped of life – yet, in order for the ocean’s

natural balance to return to a semblance of its previous condition at least

forty percent of its area would need to be set aside in perpetuity.[xxiii]

Such a step is totally incompatible with the current ambitions of this culture:

it will not happen. Similarly, if a third (to be conservative) of all of the

major land habitats on Earth were to be set aside, not only would many of

civilization’s processes have to halt, or at least contract significantly, but

those countries with larger proportions of those key habitats within their

borders would not accept having to take on the “burden” of setting aside

potential economic resources. The extreme difficulty experienced by such groups

as The Wilderness Society (in the USA and Australia), Greenpeace (in Brazil) and

the International Conservation Union to increase the amount of land set aside

from agriculture and other development, and strengthen the level of protection[xxiv]

in the face of determined government and corporate opposition, makes this all

too clear. Once again, though, Setting Aside is an inevitable consequence of

following the suggestions set out in this chapter.

Active Restoration is all that is

left; and you would be forgiven for thinking that there is hope for this

methodology, given the types of suggestions coming from corporations,

authorities, scientific institutions and other groups of people. Ideas include

seeding the ocean with iron to restore levels of carbon absorbing plankton[xxv];

replanting rainforest areas with native species; sucking carbon out of the

atmosphere and into the ocean basin[xxvi];

and instigating a process of “managed retreat” in salt marshes. Predictably,

all of this is insufficient at best, and cynical profit-mongering at worst. The

insufficiency is simply because the scale of environmental degradation being

carried out in the name of economic growth dwarfs even the most ambitious plans

of the proponents of active restoration. Much of the “restoration” work is

in the form of the heralded “techno-fix”: the idea that the tools of

Industrial Civilization can be used to build solutions to the problems of

civilization[xxvii].

The two fundamental flaws with techno-fixes, though, are that (a) they are

almost all profit-motivated, backed by corporations who have no intention of

reversing the damage done and (b) they assume that technology is an adequate

replacement for natural restorative processes, further widening the

disconnection between humanity and the real world.

Now, I’m not suggesting for a

moment that restoration is unnecessary, nor is it the wrong thing to do, but it

must be carried out in such a way that it complements natural processes. I have

a small meadow at the bottom of my heavily-wooded garden, which I have planted

with native grasses and flowers, and which I allow to grow in what ever way it

likes – a tiny memento of the wide meadows that once crossed southern England,

but something positive nonetheless. Managed retreat to restore salt marshes is a

good thing, and I can think of few things more satisfying than breaching the sea

walls that once allowed farmland to reign over the coastal ecosystem. Even some

of the more unusual ideas, such as burying biomass in the form of whole trees[xxviii]

or far more stable biochar (charcoal) have their merits but, as with the

processes of unloading and setting aside, they are only going to achieve

anything substantial in the context of Industrial Civilization becoming a thing

of the past. Do what you think is right and encourage others to do the same; but

never forget that restoration is just a stepping-stone to our real future.

Civilization is not going to go down

without a fight, and the forces unleashed can be truly terrible if the past and

current behaviour of governments, their corporate owners and their military

marionettes is anything to go by. In Chapter Thirteen I wrote: “The laws in

each country are tailored to suit the appetite of the population for change”.

This statement is especially relevant to sabotage: if the ruling Elites feel

that their beloved system is under threat then they will do their best to

suppress this threat. This suppression may be carried out legally and visibly,

or illegally and invisibly. Public activities that were once permitted will be

criminalised, and anyone that directly challenges the stability of the machine

will be taken out of harm’s way and, where necessary, made an example of.

It would be reckless of me not to

tell you this.

The system has legitimised all of its

efforts to fight back and suppress opposition because the vast majority of

people who are subjected to its activities are fully paid up members of

Industrial Civilization. It is “right” that civilization maintains its

stability because without stability, civilization collapses and can no longer

impose its will upon the population. Does that sound like a coherent argument to

you? In all truth, that really is the best argument civilization has for its

continued existence: it has to be maintained because it has to be maintained.

Even a heroin addict, shooting up to get the fix that they agonisingly crave

knows that their habit will eventually kill them. Even a lifelong nicotine

addict will admit that smoking is bad for them and they should stop. Hands up if

you think Industrial Civilization should be stopped.

*

* *

I take no great pride in knowing that

for a large part of my working life, over the last five or so years, I could

have caused a breakdown in the global economy; yet I chose not to make this

happen of my own accord. My position placed me in charge of key data centres,

front line IT security and technical disaster recovery mechanisms, the failure

of which would have caused major disruptions in the global financial trading

engine. I could have been a hero of the anti-civilization movement: but no one

would have known my name, and no one would have found out what I did. That’s

not why I didn’t do anything, though.

My lack of motivation to make the

change – to sabotage the global economy in some way – was largely down to

living, for many years, the life of the industrial worker; a slave to my

mortgage and to the system that told me that this was the way it had to be. I

wasn’t connected enough; I wasn’t angry enough; I thought this was just the

way it had to be. I guess there are

lots of people in the same situation I was: perfectly poised to screw up the

system in some way, but not sure if it is the right thing to do.

Maybe you’re in that boat, but

further down the river: informed, resourceful, connected, angry…how do you

decide whether it’s the right thing to do?

It comes down to Risk and Reward: the

Risk is essentially the sum total of the fallout that could occur as the result

of your actions; the Reward is the extent to which Industrial Civilization and

its ability to desecrate the Earth, has been weakened. When it comes to Risk,

you must go into things with a clear mind – you may have a rabid hatred for

some part of the system, but you still need to take responsibility for your

actions: will anyone die or be seriously harmed as a direct result of what you

do, and are you prepared to take on the responsibility for the harm you may

cause? Reading ahead, for a moment, if you take Rule Four into account, you are

very unlikely to encounter this kind of moral dilemma; the vast majority of acts

of sabotage that are likely to be effective are small acts that are part of a

larger, beneficial, whole – small acts that, in themselves do not cause moral

dilemmas. If you do encounter difficult choices, though, then Reward can play a

part.

Reward is a measure of the net

improvement in the long-term survival of humanity; based upon the improvement in

the condition of our natural life-support machine. It is most certainly not

about fame and glory. Few, if any, people are qualified to judge whether an act

of sabotage has sufficient reward to justify a high degree of collateral damage;

the best advice I can give is that for all acts of sabotage – large or small,

morally-complex or not – always abide by Rule One.

Rule One: Ask

yourself, “Is it worth it?”

Though the battle-worn troops of

World

War II resolutely denied Europe ever had a “soft underbelly”, Winston

Churchill nevertheless piled the combined forces of the Western Allied armies

into North Africa, across the Mediterranean and into southern Europe in

1943. The Russian forces, along with the Russian people, died in their millions

to hold off a rampant Axis army on the Eastern Front; while all the time the

Allies were working their way northwards, peeling off division after division of

German soldiers, weakening the Nazi defences as they went. Only after Hitler’s

fighting machine had been diminished through a combination of eastern attrition

and southern guile was it possible for the D-Day landings to take place on the

northern coast of France. Beating the unbeatable was a slow, but highly

calculated process: at no point after the disastrous attempt to land at Dieppe,

did the Allied forces ever attempt a direct assault upon a full-strength enemy.

A good computer hacker will spend a

large amount of time not only planning the attack methodology (this is known as

“scoping”) but also ensuring that once the attack has been completed, no

trace of it remains. This is not too difficult if the attack is a quick “smash

and grab” to extract information, change data or bring down all or part of an

IT system; where it gets difficult is in the more destructive and less

reversible hacks – those that install some kind of mechanism that allows the

hacked system to be remotely controlled or re-entered easily though a “back

door”, or those that are designed to keep on attacking the system

automatically. The best way a hacker can cover his or her tracks is to make sure

there is someone on the inside helping them. There is no way of telling how many

times insiders have been used to assist with or wholly carry out such attacks,

but you can be sure that it is far more than companies and government

departments are willing to disclose: after all, who would want to reveal that

their own employees can’t be trusted? In fact, because IT systems have become

among the most critical components within all the major corporate and political

institutions, Industrial Civilization is increasingly at the mercy of hackers

and, by extension, keen saboteurs. There are many different types of sabotage:

they all need to be carefully planned out.

Rule Two is: Don’t

go blundering in – plan your approach.

I was in a perfect position to, at

least partly, sabotage the economic machine, but I would have been a prime

suspect due to my multiple positions of authority and my well-known

environmental leanings: if caught my first action may well have been my last.

The best large-scale saboteur has all of the assets mentioned earlier, but is

also the one person whom no one will ever suspect – who has no obvious motive

and is seen as unlikely to ever exploit his or her position. Dmitry Orlov, an

authority on the collapse of the Soviet Union, describes it this way:

To do it right, you

have to get paid to do it. Good industrial sabotage is indistinguishable from

black magic: nobody should know that it was sabotage, or how it worked,

especially not the person actually doing it. The absolutely worst thing that a

half-competent saboteur can be accused of is negligence, but it really should be

more of a "mistakes were made" sort of thing.[xxix]

It is no accident that the most

effective forms of sabotage are carried out from inside – as Bruce Schneier

writes: “Insiders can be impossible to stop because they’re the exact same

people you’re forced to trust.”[xxx]

Exploiting the trust of someone may feel morally reprehensible, but remember

that you are being trusted by someone who is a willing (and possibly eager)

participant in the most destructive culture ever seen on the face of the Earth.

The most recent UK Labour Government

was almost brought down through leaks made by individuals within its own

departments: the leaks concerned something that had forced countless people to

reflect on their inner feelings about the morality of a single activity: the

Iraq War. Dr David Kelly – the only named source in the revelation that a

dossier, specifically produced for the Blair Government as a case for going to

war, was hopelessly inaccurate – paid for his “going public” with his

life. Whether he died at his own hands, or those of other agencies will never be

known for sure, but Kelly was not the only source of leaks concerning the

“Dodgy Dossier”, and was certainly not the only source of the many leaks,

off-the-record conversations, anonymously sent memos and uncensored government

files related to the Iraq War. When something like a questionable war, a

genocide or a global ecological catastrophe invokes the morals of people in

positions of trust, they can, and will use whatever tools they have at their

disposal to undermine whatever is the cause of the problem. If the protagonist

(or saboteur, if we are being accurate here) is able to remain in that position

of trust, much as Cold War spies were able to pass on secrets for years

undetected, then they are all the more effective.

Rule Three is: Don’t

get caught.

But what kinds of sabotage are we

talking about? No doubt it’s a major achievement to bring down a corrupt

government, but it will only be replaced by one that operates along the same

lines as its predecessor – to promote the “need” for economic growth and

to spread the influence of Industrial Civilization around the world on behalf of

its corporate masters. Bringing down an oil company or even a single refinery

will, indeed, cause a halt in the production and sale of a large amount of

climate changing hydrocarbons and, if the company or refinery is large enough,

could trigger economic unrest; but there are other oil companies and many more

refineries, and there are always powerful institutions, and huge numbers of

deluded people, who will ensure that the oil keeps flowing – at least until it

runs out. The primary targets for sabotage, if enough people are to carry out

the tasks necessary to reclaim the Earth for those that actually want to

survive, are the things that are stopping people from connecting with the real

world: the Tools of Disconnection. If you read Chapter Thirteen, you will get a

pretty good idea of the kinds of things that should be targeted.

Rule Four is: Concentrate

your efforts on the Tools of Disconnection.

The first reason for this is that

disconnection is the biggest problem humanity is facing, and we are trying to

deal with the root of the problem here. It may be satisfying to burn down a

garage full of SUVs if you have a virulent hatred of gas-guzzling road

transport; but these places are insured and there are plenty more SUVs where

they came from. In the context of reconnecting humanity, such actions are only

symbolic. Far better to sabotage the advertisers and marketing media that

encourages people to buy SUVs in the first place; far better to sabotage the

government agencies and trade bodies that ensure that vehicle sales and

production remain a high priority; far better to sabotage the efforts of the oil

and motor companies in convincing people that climate change is nothing to do

with them, and even if it is, the disappearing ice-caps are not really that much

of a problem.

The second reason to concentrate on

the Tools of Disconnection is that the laws that protect the global economy, and

the forces that ensure the global economy remains the primary concern of

humanity, are currently focussed on protecting the symbolic elements of

Industrial Civilization. I don’t believe for a moment that these forces

won’t move to protect the Tools of Disconnection if, and when, a concerted

sabotage effort takes place; I don’t believe for a second that laws will not

be made to ensure those of us who want to opt out of the system are

“encouraged” to stay: but for the moment, it is the traditional targets of

the symbolic protester – the buildings and vehicles and individual “elite”

members of society, for example – that are best protected. If you attack a

corporate headquarters or chief executive then you will be stopped and probably

imprisoned; if you divert or copy all confidential documents coming out of a

corporate lobby group to a publisher of “subversive” materials or a local

friendly radio station then who is going to come off worse?

I am not going to dwell on the

numerous methods of sabotage open to those who have the motivation and the means

to carry them out – those people (of which you may be one of) are almost

certainly far better equipped than me, and also know how to do it far more

effectively and secretively than I could outline in a book of this nature –

but I will reiterate what I think are the four key rules of sabotage, should you

chose to take that path alongside the other things I have suggested in this

chapter:

1.

Carefully weigh up all the pros and cons, and then ask yourself, “Is it

worth it?”

2.

Plan ahead, and plan well, accounting for every possible eventuality.

3.

Even if you understand the worth of your action, don’t get caught.

4.

Make the Tools of Disconnection your priority; anything else is a waste

of time and effort.

*

* *

One question still remains unanswered,

but has been well covered by Derrick Jensen in his Endgame books: “How can

just a few determined saboteurs make it easier for the rest of humanity to

reconnect with the real world?” The simple answer is that far fewer people

have to make the first move than you might suppose. As Jensen revealed during a

conversation with a former military officer:

They don’t have

to break everything in sight. All they have to do is give the first in each line

of dominoes a hearty enough heave. Once the reaction has achieved a critical

threshold a fire will feed itself and grow uncontrollably. Part of the key is

winning the minds of the people who would otherwise plug all the machinery[xxxi]

right back in again. Once they realize they can actually walk away, without

repercussions, they’ll be able to exercise their human freedoms in prodigious

ways.[xxxii]

If you hark back to the discussions

about the fragility of civilization then it becomes less of a pipe dream and

more of a reality to think that a few people can start the dominoes tipping. And

anyway, who is to say that thousands of people are not already partaking in a

healthy slice of disconnection sabotage? Even if you simply post a dodgy

internal corporate memo to your local newspaper in an unmarked envelope in a

post box far from your home, or even if you just paint “Liars!” on a

billboard near a busy road junction in the dead of night, you are already

joining the swelling ranks of the saboteurs.

Educating

Knowledge is power, and the greatest

threat to Industrial Civilization is a knowledgeable population. As we saw in

Part Three, the huge effort undertaken by countless authorities over many

centuries to ensure that information is controlled, bears testament to the

danger they see of information falling into the wrong (or rather, the right)

hands. Remember, we are not talking about conspiracies and dark secrets here,

but basic information about the way companies and governments operate on a

day-to-day basis; objective information about the damage we are doing to the

very environment we need to remain healthy in order for us to survive; the way

in which we are being systematically disconnected from the real world; and the

simple but devastatingly effective measures everyone can take to change all of

this. But it doesn’t stop there.

Just as sabotage is vital in cutting

the arteries of civilization’s disconnection machine, education in its purest

form is vital in healing the deep divisions that have been created by that

machine. Real education is a form of sabotage: it sabotages the education system

that turns children into potential employees, potential voters and potential

consumers. Children, and adults for that matter, need to become world-wise,

connected and able individuals; they also need to become people who want to work

together, not as economic units, but as communities of people striving to

achieve something far more real than anything Industrial Civilization could ever

offer them. Not only is such an education far more relevant to the real world,

it is imperative that people are equipped with the skills to survive whatever

will happen in the next few decades. David Orr, starkly laid out one of the

future decisions we will have to make following the inevitable collapse of

cities, in a 1994 lecture:

The choice is

whether those returning to rural areas in the century ahead will do so, in the

main, willingly and expectantly with the appropriate knowledge, attitudes, and

skills…or arrive as ecological refugees driven by necessity, perhaps

desperation. For all of the fashionable talk about cultural diversity, schools,

colleges, and universities have been agents of fossil energy powered urban

homogenization.[xxxiii]

As a people, we are losing basic and

vital skills with frightening ease; partly out of ignorance, but mainly because

we have been made to believe that civilization will look after us, provide for

our every need and make such skills as growing, building, cooking and caring

obsolete. We have become incapable of looking after and thinking for ourselves.

One of your tasks as an intelligent, knowledgeable and connected person is to

ensure that useful information stays out there – in the minds of as many

people as possible.

The classrooms in the education

systems of Industrial Civilization only provide sufficient knowledge to turn

humans into good workers; that is not where the educating should take place. It

should take place in the homes of families and friends; in pubs and restaurants;

in sports venues; at pop concerts and music festivals; in parks, woods, fields,

beaches and on the street; in trains and buses; in offices, shops and factories;

even in playgrounds. Person to person, unfiltered and uncensored – just

information that can be discussed, debated, added to, written down, remembered

and passed on again and again. You need to keep this information alive and

accurate; you need to keep it interesting and relevant; you need to be a teacher

because, like it or not, the system is not going to educate anyone on how to

live in a world where the system is not in charge.

Level

Two: Ways To Accelerate Change

This is the point when most

environmental guide books tail off into a happy conclusion, generally along the

lines of, “If we all follow these suggestions, the world will be a better

place”. That is, of course, complete garbage. For a start, the recommendations

in these guide books are generally no more radical than installing a wind

turbine on your roof, or lobbying your government representative / friend of the

global economy for change. Also, as I said in the last chapter, the assumption

that everyone reading the book (let alone a large enough number of people to

really make a difference) will follow the recommendations is foolish at best. A

conclusion at this point would make no sense at all – you can’t change a

society if only a tiny minority of people are prepared to change themselves. I

know that the things I have suggested, as well as those I have warned against,

will only initially be taken up by a very few people: what is needed is a way of

propagating that change to a far larger group in the shortest time possible.

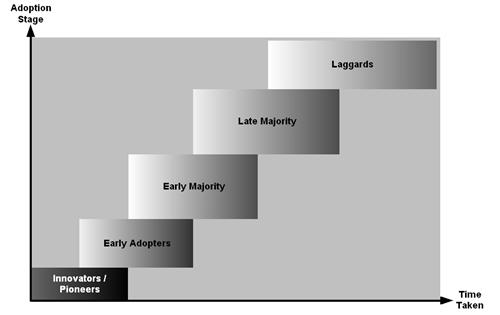

Innovators, Early Adopters, And

The Rest

If you have read up to this point of

your own accord, and are prepared to take on the challenge of using various

methods to gradually crumble Industrial Civilization, then that makes you an

Innovator. The first way of accelerating the change process is based upon the

Diffusion of Innovations theory, which the American sociologist Everett Rogers

developed into something far-reaching and rather brilliant.[xxxiv]

An Innovation can be anything that has not been done before; whether that be

adopting a new technology, watching a new television program or changing a

society. Rogers proposed five different groups of people through which the

innovation has to pass before an entire population can be said to have adopted

it: Innovators (sometimes called Pioneers), which account for around 2.5 percent

of the population; Early Adopters, 12.5 percent of the population; Early

Majority, 35 percent; Late Majority, 35 percent and, finally, Laggards who are

the last 15 percent of people to take on an innovation. The percentage figures

can change depending on the type of innovation and also the nature of the

population; but what is more important is that the five groups each describe a

time-lag: the Early Majority will not adopt an innovation until the Early

Adopters have, and so on.

On its own, that seems simple enough,

but what makes things more complicated is that each individual within each group

usually has to go through a number of different phases in order for their

personal adoption to be achieved, as follows[xxxv]:

1.

Knowledge

– person becomes aware of an innovation and has some idea of how it functions,

2.

Persuasion

– person forms a favourable or unfavourable attitude toward the innovation,

3.

Decision

– person engages in activities that lead to a choice to adopt or reject the

innovation,

4.

Implementation

– person puts an innovation into use,

5.

Confirmation –

person evaluates the results of an innovation-decision already made.

People in one group are unlikely to

start their adoption process until those in the previous group have, at least,

started their Implementation phase, and probably not until the Confirmation

phase: “Leaps of Faith” are as uncommon as they are risky. The Confirmation

phase is when the adopter decides whether they are happy with the outcome of the

adoption, and is in the best position to encourage others – friends, family,

colleagues, neighbours and so on – to start the adoption process themselves.

If the members of one group never reach the Confirmation phase, there is very

little chance of the innovation passing to the next group.

With all that said, it sounds as

though any major change in society towards a survivable future is going to take

an age, especially when you consider the enormous pressure constantly placed on

individuals to ensure that they don’t change at all. This is where you come

in.

*

* *

I said in the last chapter that some

of this theory was a bit dry so, rather than plough on and risk losing you

through sheer boredom; I’m going to explain how this needs to work in

practice. I’m going to describe the most important innovation of all: the one

that comprises the raft of different radical measures described in the last

section; the one that people need to adopt in order for them to become part of

the solution.

The difference between a population

deciding to watch a new television programme and them taking on a completely new

way of living is profound: for a start, switching over a TV channel, even

arranging things so you are near to your television at the time the programme

starts takes very little time – changing your life can take years, especially

if you are a deeply ingrained “consumer”. More obviously, persuading someone

to change their life as opposed to changing their TV channel requires a lot more

effort: something I will deal with in the Level Three section. Figure 3

shows the process graphically, with the thin bands indicating the smaller

population groups, and the increasing adoption time for each group indicating

the additional effort required for a more ingrained person to change their life.

The “Innovators / Pioneers” group is highlighted because nothing can happen

until this group begins adopting the change. There is no absolute time scale;

you will see shortly that it is almost impossible to predict how quickly the

population will change because there are so many factors to consider.

Figure

3: Simplified Diffusion of Innovations graph for fundamental life changes

(Source: Author’s own image)

Consider lighting a fire: you can’t

send a spark to a large, dense piece of timber and expect it to ignite – you

have to start with the smaller, more reactive materials. First the newspaper or

tinder catches; then the small sticks – the kindling – begin to burn; then

the larger pieces of wood and, when the flames have reached a high enough

temperature, the logs will start to burn. You end up with a powerful, intense

fire, hot enough to set light to almost anything that is placed near to it. Now,

what if you are lighting the fire under different conditions: in some cases your

materials may be dry, you have a good air flow but not enough wind to blow the

flames out; compare this to a fire made from slightly damp materials – it’s

raining, the wind is blowing hard.

In Level One, I suggested lots of

different changes; some of which are harder to achieve than others. Change

isn’t going to happen in one big bang, even among the Innovators; it will

require different levels of effort and different timescales, so it’s important

to keep plugging on, even when you have made what you consider to be big changes

in your life. When you have made a significant change – say you have stopped

being a conspicuous consumer or you have stopped flying and driving entirely –

that is a good point to start influencing the people in the next phase, while

still continuing with your personal efforts. I know it sounds a bit convoluted,

but it’s actually a very natural way of doing things; after all, your friend,

who may be quite keen to change is more likely to be put off from changing when

they see what a massive gulf there is between you and them. Instead, if you are

in a position to guide your friend through the same change you have just

completed, they are far more likely to go along with you; and also pass on their

more comfortable (albeit quite radical) experience to others.

It is important to also understand

that you are very unlikely to persuade someone to change if they are two or more

phases behind you: I long ago gave up trying to discuss environmental and social

changes with many of the people I knew – the conversation might have been

interesting, but there was no chance of them agreeing to actually do anything

about it. Miracles do happen and people do have moments of revelation, but the

best strategy – as shown by the abject failure of groups like Greenpeace and

Friends of the Earth to change a defiant public en masse – is to concentrate

your efforts on those most likely to be persuaded. Any other approach flies

in the face of social theory and, to be honest, common sense.

Finally, I just want to mention

something that was pointed out by a close relation just a few days ago: how do

you deal with the situation where someone is trying to persuade you not

to change? This is all about peer pressure, and peer pressure can be extremely

toxic at its worst. A person who decides to go vegetarian, for instance, will

come up against not only the system itself, using its Tools of Disconnection,

but lots of people who might persuade them to “just have a bit of meat” or

to not change on the grounds of health, convenience and the multitude of other

reasons people give for avoiding a change in their diet. I’m not suggesting

for a second that you should avoid your friends or relations (although it might

be a good time to consider who your real friends are), but I would say that

times like this require a great deal of self-confidence, and not a little tact.

It is possible that the people asking you not to change are actually closer to

changing themselves than they will ever admit – as Carol Adams writes, with

reference to people that try to sabotage vegetarians: “Saboteurs may be the

group most truly threatened by vegetarianism. That’s the last thing they can

admit to themselves or you.”[xxxvi]

Remember when I said earlier on that