|

Chapter 11

Why Connect?

In

January 2008, the amount of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere touched 385 parts

per million[i].

That same month, Dr James Hansen of the Goddard Space Institute in New York gave

a short presentation to the Royal College of Physicians in London[ii]:

in it he stated that, based on historical data comparing atmospheric carbon to

global temperatures, the maximum safe level for carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

was 350 parts per million – beyond this, the Earth’s natural systems would

change irreversibly. As I type these words, the volume of CO2 mixed

with the air in the chilly back room I am sitting in exceeds this safe limit by

10%. I am inhaling something that is already capable of removing the Greenland

ice cap and raising the level of the ocean by seven metres[iii].

Seven metres? I go to a web site that shows what this would mean to the

world’s coastal regions[iv],

click on the drop-down arrow and select “+7m”.

The

web site knows which country I live in: much of the fertile growing land in

eastern England is under water along with half of the Netherlands. I scroll the

map down and zoom out a little: most of Europe is safe at the moment. Across the

Atlantic the Mississippi Delta is flooded – the recovering towns and cities of

southern Louisiana have taken their last breath. The playgrounds of the Florida

Keys and Ocean City are gone, along with great swathes of the eastern seaboard.

I scroll eastwards. South East Asia is hit terribly: Shanghai and Hong Kong are

just small islands in a sea of floodwater; Bangladesh sees permanent floods

beyond the imagination of even those who experienced the catastrophe of 1970.

And this is just the calm, tidal ocean, without storm surges and hurricanes;

quite unlike the tempestuous one we can look forward to in the next fifty years,

even with the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere unchanged, at just 385

parts per million.

Carbon

dioxide accounts for about sixty-five percent of all anthropogenic global

heating that is taking place[v]

(the word anthropogenic just means, “made by humans”). Carbon dioxide is

especially significant, not only because it is responsible for a large portion

of the unnatural Greenhouse Effect but also because it is the one gas whose

level is continuing to rise while the others – such as methane and nitrous

oxide – are relatively controlled, for the moment[vi].

The lack of carbon control is everywhere: from the belching SUVs and

power-hungry air conditioners of high-tech USA, to the teeming coal-fired power

stations of newly commercial China and India; from the fuming peat left burning

after the Indonesian forests were scorched, to the reeking oil sands of Canada.

Oil, wood, coal and gas are being ignited across the world to feed a growing

appetite for more of everything. More technology; more heat; more cold; more

meat; more money; more greed; more profit; more speed; more vacations; more

need.

More

deserts.

More

flooding.

More

storms.

Less

ice.

Less

food.

Less

life.

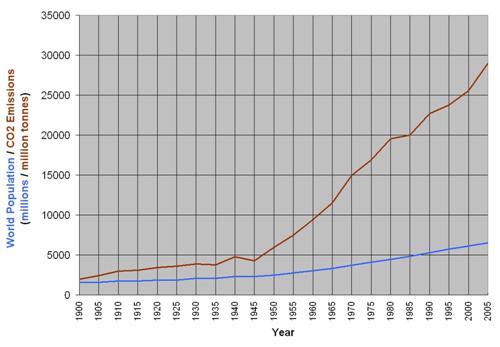

Figure

1: World Population vs. World Carbon Dioxide Emissions (Source: Author’s own

image, derived from various sources)

In

1900 the world population stood at about 1.5 billion people, about the same as

the current population of India, Bangladesh and Pakistan combined. In the same

year, historical statistics show that the amount of carbon dioxide being

produced by fossil fuel burning was 1.9 billion tonnes[vii],

or just under a third of what the USA put into the atmosphere in 2004. By the

beginning of the Second World War, the population had risen considerably, to 2.3

billion, an increase of over fifty percent; by the same year global carbon

dioxide production was around 4.7 billion tonnes. The war took the edge off

industrial production in the West so that, by 1945, emissions had fallen by

nearly eleven percent, but it had taken a global event that directly caused

fifty million deaths for civilization to reduce carbon dioxide production by

just a tenth.

The

upturn in population growth that I described in Chapter Eight has its

significance in the way it took human numbers from a relatively modest 2.5

billion people in 1950, up to 6.5 billion in 2005; an increase of 160 percent in

just fifty-five years. Over that same period of time carbon emissions grew from

six billion tonnes to twenty-nine billion tonnes, a leap of extraordinary

proportions: no less than 380 percent, or nearly two and half times the rate of

population growth. This was achieved even with almost an entire decade of carbon

stability in the 1980s.

From

the first graph it is evident that population growth and carbon dioxide

emissions do have something in common, but the increase in human numbers

doesn’t go anywhere near explaining where all the carbon is coming from. Once

I had fed in some economic figures from the World Trade Organization[viii]

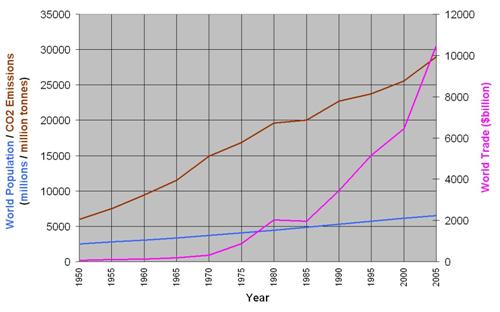

and produced Figure 2, though, something was startlingly clear: it is

not population growth that is driving greenhouse gas emissions, it is money.

The

graph, which illustrates the period between 1950 and 2005, has sprouted another

line, the pink one, showing how trade between different countries boomed over a

period of 55 years. Trade is affected by a great number of things, but the most

important of them is whether there is a market for something or not: if there is

a market then a producer can sell things to a consumer. The market for something

will eventually become saturated unless the producer can find ways of making the

consumer interested in buying more of a product, but it is often easier to open

up new markets for the same thing, which is one reason that trade has rocketed

since 1985. I’m getting ahead of myself, though – what is important here is

the uncanny similarity between the shapes of the Emissions line and the Trade

line.

Figure

2: World Population vs. World Carbon Dioxide Emissions vs. World Trade (Source:

Author’s own image, derived from various sources)

The

post-war boom in the industrial West; with its acceleration in the use of

consumer goods – such as televisions, vacuum cleaners and refrigerators –

the rise of the “car culture” and an upsurge in the number of new houses;

pushed global carbon emissions up by 250 percent in just 25 years. Coal was the

fuel of choice for electricity generation, and massive oil discoveries in the

Middle East during the 1950s and 1960s, including seven of the largest oil

fields ever found[ix],

meant that cheap fuel, almost literally, drove consumption through the roof. The

oil crisis, in the 1970s, and two major economic recessions in the 1980s pushed

emissions growth down a little, but still it sped ahead of population growth,

and by 1985 emissions beat population by a factor of four to one. Bearing in

mind that they had been almost neck-and-neck in 1900, this is phenomenal growth

by anyone’s standards.

Between

1950 and 1970, international trade (imports and exports) grew from $60 billion

to a still relatively modest $317 billion: growth of 413 percent in 20 years is

impressive, but nothing compared to later on. International trade started to

climb rapidly after 1975 – because the graph only shows trade between different

nations, the freeing up of international markets during the 1970s is

particularly visible, as is the massive global recession in the 1980s, and the

explosive growth in the international trade of consumer goods since 2000. These

variations in world trade[x]

between 1975 and the present day are closely matched by changes in carbon

dioxide emissions – with the notable exception of the early-1990s, when the

smokestacks of much of Europe stopped belching following the collapse of the

Soviet Bloc, and the emergence of natural gas as a cleaner generator of

electricity. This blip was not to last long.

Despite

promises by many governments and businesses to control their emissions, the

slope is steepening. This inflationary jump is primarily the result of

manufacturing being shifted from rich nations in which labour is relatively well

paid, to poorer nations – in which workers are generally paid a pittance –

that generate electricity by far dirtier means. The fruits of this transfer of

labour are then laboriously transported back to the rich nations that buy the

goods, thus producing even more carbon dioxide[xi].

This is compounded by another lucrative export: the industrial West’s love

affair with cars, household consumer goods and a meat-rich diet is no longer the

preserve of rich nations – it is increasingly seen as something that all

people have the right to be a part of. The fact that this behaviour fattens the

wallets of business leaders in the West is not entirely coincidental.

* * *

The

connection between money and carbon emissions, worrisome as it is, is just one

of many social, political and economic connections that we encounter on an

almost daily basis[xii],

often without realising it; but there is a far more important connection that we

now need to consider – one that is the subject of the rest of this chapter and

the one after that. It is so important that I’m going to simply refer to it as

The Connection.

The

Connection

Do you

have a spare shoe you can look at? Any shoe, it doesn’t really matter as long

as it fastens using laces. If you are wearing one then that will be fine. If you

need to fetch the shoe then please get it now, I won’t go anywhere.

Okay?

Now

look carefully at the lace – undo it if it has a knot or a bow – find the

right-hand end and hold it in your hand. This end is you: a human being, no

different to any other human being on Earth, whatever culture you live in,

whatever race you may be or language you may speak. Now find the left-hand end,

and hold on to that as well. This end is everything else in the world: from the

smallest atom of carbon, to the microbes, the worms, the bees, the fish, the

trees, the forests, the oceans and the atmosphere that you are breathing in.

Two

ends of a piece of string, so close together: one totally dependent on the

other. If you have read this far you will know by now which end is most

dependent on the other. The webs and chains that lock lives together in a

symbiotic embrace exist in order that life on this planet can be as complex and

varied as it is. Humans would be nothing at all without the ancient history of

interconnections that have been made between different species. Most of the

strands have let go, fallen beside the four billion year path for others to

replace them and take the strain; but the new strands still hold on, for if they

didn’t then humanity would fall like a sack of rocks into a deep well.

Splash!

As easy as that.

That

we should care about our descent into the icy well water and our untimely

extinction is beyond doubt. We are survival machines and we exist to continue

our species – there is no greater motivation than the simple urge to stay

alive, and for that reason it is simply not possible to be human and not care

about our fate. It follows that it is simply not possible to be a free

thinking human being and not care about what is happening to the planet that we

depend on.

Take

another look at the shoelace. Follow each end downwards as the woven strands

move in and out of the holes, intersecting, touching each other and finally

meeting at the end. The two ends always were together. From the origins of life

our fate has been intimately tied up with the fate of the rest of our Earthly

companions, and there is nothing you can do about it.

* * *

Would

you risk your life to save a tree along the street you live in; would you put

yourself between the trunk of a plant and a chainsaw, axe or machete – however

slender that plant may be – in order to preserve it for another day? If it

were woodland near to your home, or even a forest at the other side of the world

that was imminently threatened with removal, would you then endanger your life

to protect it?

A

British environmental activist I have known for years was narrowly saved from

death by an Oxfordshire police officer. It’s ironic that the reason the police

officer had to stem the blood gushing from an artery was that the artery was

severed while “A” was trying to escape from a police cell. “A”

desperately wanted to escape in order to return to the scene of his “crime”

so he could once again hold up tree felling work; felling work that was taking

place in order that a power company could fill a thriving lake with the spoil

from a coal-fired power station. My friend thought little of his fate, except

that the trees must be saved. His attempts to stop the trees being cut down were

deemed illegal, and so he was arrested and sent to the police cell in which he

nearly died. Despite his brush with death, he has since told me that he would do

it again: “I would try and save life again, risking my own life, because all

life is worth saving.”[xiii]

The

temptation, in societies where the fate of species other than humans is regarded

as incidental, is to label such behaviour “extreme”, or even

“psychotic”. Certainly my friend was labelled both an extremist and a

“tree hugger”, and punished for his actions. The term “tree hugging” is

often used as a disparaging term to describe environmentalists, like my friend,

who greatly value the distinct and irreplaceable service that trees carry out

for the biosphere. In fact, by definition, to be a Tree Hugger is to be someone

who would place yourself at the mercy of whatever humanity might exist in the

minds of a person determined to destroy the tree, which you are embracing. The

Garhwal Hills of northern India contain a number of tribes whose lives have

changed little in 1500 years and probably far longer[xiv].

They also contain the origins of the Chipko Andolan (literally, “hug the

trees”) movement. In 1973, following decades of successive removal and

partitioning of the forests by both the British and the Indian governments –

forests that the indigenous people depended on for their well-being – the

patience of the Garhwali finally ran out: the villagers had been refused

permission to cut twelve trees in order to make tools while, simultaneously, a

sporting goods company was granted permission to cut far more trees from the

same forest to make tennis racquets.

The

women of the village, in particular, started protecting the trees with their own

bodies, trying to grab the axes of the loggers: risking their lives at the hands

of those who had been charged to remove the trees that the Garhwali so badly

needed to be managed responsibly and sustainably. A state officer, who was under

the impression that the government owned the trees, not some upstart tribal

women, attempted to confront the protestors:

It was

time to settle the matter once and for all. He and his entourage went into the

forest to lay down the law, but instead witnessed a sight that was both

fascinating and disarming: hundreds of women, more than he could count, milling

about among the trees, singing songs and chanting, many with infants strapped to

their waists and children at their feet. Realizing that to lay down the law

would require some kind of brutal offensive against all of the women and

children in the area, he left chastised and embarrassed.[xv]

Do

you feel that the actions of the Garhwali women in India were any less, or more

extreme than those of the British environmentalist? Again, it would be tempting

to suggest that the Chipko Andolan were taking unnecessary risks in order to

save some trees, but their lives depended on the forests remaining intact; to

provide a sustainable source of wood for cooking, heating and tool making; to

stabilise the ground and prevent mudslides in the mountainous terrain; to ensure

that the waters remained fresh and constantly available. Most people would agree

that some kind of activism would be justified – but would you risk your life

to maintain a way of life in the face of creeping development, and the promise

of a more modern lifestyle: the kind that the British environmentalist has no

choice but to lead?

The

Garhwali people have a village-based culture; farming and using the land around

the villages in the most sustainable manner they can. Without treating the land

in such a way their distinct way of life would have been wiped out long ago.

Because of their similarity to some more recent cultures, the Garhwali are able

to make minor adaptations to their lives, without greatly affecting their

cultural integrity: but there are limitations, and large, enforced changes

would, as with so many other societies before them, cause irreversible damage.

The

tribal people of West Papua live in a manner that is entirely alien to most of

modern humanity. According to Bernard Nietschmann: “The people of West Papua

are different in all respects from their rulers in [Indonesia]: language,

religions, identity, histories, systems of land ownership and resource use,

cultures and allegiance.”[xvi]

Imagine, for a moment, living in such a way that you had no concept of outside

rules, beliefs and culture; when, suddenly, the land you have nurtured for

centuries with delicate care is ripped away from you to be handed to a

corporation intent on mining it for metals, leaving the land in tatters and

thousands of tonnes of toxic spoil leaching poison into the ground. This is

precisely what happened in the years following 1967 under the despotic

leadership of President Suharto of Indonesia (who also forcibly took control of

the country following a military coup in 1965). Two large mining companies from

“democratic” nations; Freeport, based in the USA, and Rio Tinto Zinc, a UK /

Australian conglomerate; were handed the mineral rights for a large part of West

Papua in return for generous donations to the Suharto regime. Despite

Suharto’s bloodthirsty behaviour across his empire, including responsibility

for the slaughter of half a million Indonesians in 1965, the CEO of Freeport,

James Roberts, called Suharto, “a compassionate man.”[xvii]

The

native West Papuans have never had the land returned to them, primarily because

there is no profit to be made in giving a peaceful, nature respecting people

stewardship of a region under which there are rich mineral resources to be

plundered. Since the 1970s the situation has, if anything, worsened with the

rise in illegal deforestation for the lucrative export of tropical hardwood,

pulpwood with which to make paper, and the palm oil from monoculture plantations

which goes into such Western essentials as chocolate chip cookies, hair

conditioner and potato crisps. Such activities – illegal or otherwise – are

actively condoned by the new democratic government and, despite the best efforts

of United Nations and human rights workers, intimidation is rife:

The

Special Representative is also concerned about complaints that defenders from

West Papua working for the preservation of the environment and the right over

land and natural resources (deforestation and illegal logging) frequently

receive threats from private actors with powerful economic interests but are

granted no protection by the police…This climate of fear has reportedly

worsened since the incident of Abepura in March 2006, where five members of the

security forces were killed after clashes with protesters demanding the closure

of the gold and copper mine, PT Freeport. Lawyers and human rights defenders

involved with the trial received death threats.[xviii]

Tree

Hugging in such an isolated and tightly controlled landscape of fear cuts no ice

with private security firms or the Indonesian government. In a world where the

media rarely takes an interest, and the public are disbarred, who is to know

whether the defenders are just being killed by the military or private security

guards? It is clear from regular observations that, where the indigenous people

have clashed with developers, the developers have always won in the long run[xix].

This puts indigenous people in a terrible dilemma: do they continue to fight for

the return of land that their entire existence depends upon; or do they enlist

the help of outside agencies or, even more controversially, rely on the

compassion of the businesses actually responsible for the land-grab in the first

place? Such compromises almost always lead, as mentioned before, to irreversible

cultural change. Their lives are on

the line, whichever way they turn. What would you do in their situation?

Figure

3: Fishing tribesman from Baliem Valley, West Papua (Source: Creative Commons

Internet image)

Defending

something that is central to your life is not “psychotic” behaviour, nor is

it “extreme”; it is simply human nature. A man who tries to take my life

from me by suffocation, by forcibly holding his hands over my mouth and nose, is

immediately locked in his own life-or-death struggle, for I would fight to the

death to retain my own life – as any sane person would. The connection between

the assailant’s hands and my own fate is immediate: there is no doubt that the

two are connected in this particular situation. In a slightly less direct sense,

the total loss of your food source, shelter or any other means of sustaining

yourself clarifies the connection between the thing that you depend upon and

your desire to survive. I don’t need to tell you this; take these things away

and it becomes obvious.

As

I said in Part Two, the City Dweller is cut off from his life support system. In

a world where more than fifty percent of humanity lives in cities this is an

ever more vital observation: as far as any hunter-gatherer, or indeed any person

producing their own food is concerned, you may as well have your source of

nutrition completely taken away from you if you have no sight or knowledge of

its origin. As you pick your ready-meal or bottle of Coke off the shelf of your

local supermarket (if that is where you shop, or what you buy) do you have any

concept of where those items come from? Certainly, the mere fact of having a

ready-meal made from numerous different and obscure ingredients immediately

distances consumers from the food they are eating; and where on Earth do

those ingredients come from? Two studies carried out in 2001 found that the

distance average food items in the USA and the UK had been transported from

“farm to fork” had risen by a factor of two and five times respectively[xx]

in just two decades. Average figures for common foodstuffs ranged from 2,500 to

4,000 kilometres – these are average figures, nothing like the longest

distances that some foods travel.

The

vast distances involved just to bring a head of broccoli or a pint of milk to

your table – sometimes between very similar types of countries, and sometimes

(and usually in this direction) from poor to rich countries – places a

psychological barrier between the person eating the food and the place where

that food was grown. Not only that, but the means of production, whether for

food or any other product of the industrial economy, has been divided up in such

a way that the different parties involved in that production can barely conceive

what the impact of their particular niche is on the environment. As Curtis White

puts it: “The violence that we know as environmental destruction is possible

only because of a complex economic, administrative, and social machinery through

which people are separated from responsibility for their misdeeds. We say, ‘I

was only doing my job’ at the paper mill, the industrial incinerator, the

logging camp, the coal-fired power plant, on the farm, on the stock exchange, or

simply in front of the PC in the corporate carrel. The division of labour…

hides from workers the real consequences of their work.”[xxi]

Not surprisingly, concern for the damage caused to the natural environment in

which the food was produced – be that deforestation for beef cattle or

soybeans in Brazil, removal of mangroves for shrimp farming in India, or the

ploughing up of wildflower meadows to grow rapeseed in the English countryside

– is muted in industrial nations, at best. To me, it is this lack of concern

that is psychotic, not the other way round.

* * *

In

April 2008, James Speth, Professor of Environmental Policy at Yale University

made the following sober, and startling remarks:

All we

have to do to destroy the planet's climate and its biota and leave a ruined

world to our children and grandchildren is to just keep on where we're going

today, just keep releasing greenhouse gases at current rates, just keep

degrading and homogenizing and destroying our biological resources, just

continue releasing toxic chemicals at current rates, and by the latter part of

this century, the world won't be fit to live in.[xxii]

When

you consider the type of changes that are taking place as a result of human

agency, across the complete range of scales in which life operates; and that

many, if not all of those changes will impinge upon your ability to survive, do

you feel connected with those life forms?

For

hundreds of millennia, humans connected tightly to the land and the life forms

their survival depended upon, because that was how it had to be. Failure to

connect was not an option; if you didn’t know how plants grew, how animals

bred, how rivers ran, how the seasons and the weather changed, then you did not

survive. In some parts of the world – the Native American tribal lands of West

Coast USA, the dense forests of West Papua, the deep valleys and jagged

mountains of northern India – these connections remain, and cling on despite

the best efforts of those who seek to gain more from the land than “mere”

survival. This connection has ebbed away from the majority of humanity, in many

cases to the extent that people feel nothing for anything humans have not

created themselves. But we cannot eat concrete; we cannot breathe television; we

cannot drink money.

Are You Ready?

The

Connection is a very personal thing. It can manifest itself as a whole range of

emotions, all of which link people with their surroundings and the things they

depend upon for their continued survival. That odd surge in the gut as you look

up into the branches of a tree; that frisson of excitement that comes from

enveloping yourself in the sea; that strange feeling that you have something in

common with the animal looking you in the eye: they are all symptoms of The

Connection. It is nothing great and mysterious; it is simply the necessary

instinct that ensures we do not damage the ability of the natural environment to

keep us alive. Failure to connect is the reason humanity is pulling the plug

on its life-support machine.

Connection

is a two-stage process: first, we must learn to connect because we have to,

because if we don’t then we die; second, we have an innate need to connect

because it is part of who we are. The whole of this chapter has been devoted to

the first stage – the clear imperative that we must connect the two ends of

the lace together – what we are and what we are doing. This is a learning

process, and for people in the early throes of Westernisation then Connecting

may be as easy as falling off a lifestyle: it is simply a case of reconnecting

with a way of life that existed not so long ago, and which still manages to

survive in pockets tragically being squeezed out by the rush to become part of a

consumer culture. For many others, the majority of people in the industrial West

who identify most strongly with a hyper-consuming way of life, learning how to

reconnect out of necessity is a struggle: most of us have never experienced

anything but the disconnected lives we inhabit.

The second stage of Connection just is. Like the invisible join between the two ends of the lace, we have always been connected, we just need to recognise how natural and comfortable it is to be this way. If you feel you are ready to reconnect, or just want to see what it is like to take the plunge from your world to the real world, then read on.

References

[i] NOAA: Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide, http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/ (accessed 4 March, 2008). Parts Per Million, or PPM, is the standard measure of the volume of carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere. Methane and Nitrous Oxide are measured in Parts Per Billion because they are present in smaller quantities.

[ii] James Hansen, “Global Warming : The Perfect Storm”, Presentation made to the Royal College of Physicians, London, http://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/RoyalCollPhyscns_Jan08.pdf (accessed 13 March, 2008)

[iii] Fred Pearce, “Greenland ice cap 'doomed to meltdown'”, New Scientist, 2004, http://environment.newscientist.com/channel/earth/climate-change/dn4864 (accessed 13 June, 2008).

[iv] http://flood.firetree.net/ (accessed 13 March, 2008)

[v] Until very recently, water vapour was not considered an anthropogenic greenhouse gas, but recent work by David Wasdell (www.meridian.org.uk) among others has found a number of feedback loops which could place the amount of water vapour very much in the our hands. Water vapour is responsible for a great deal of the natural Greenhouse Effect, which makes life on Earth possible.

[vi] With the increase in ruminant animal consumption methane levels are almost inevitably going to start to increase again after the recent drop in levels caused by drying wetlands (http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2006/s2709.htm: accessed 31 March 2008). Nitrous oxide levels could also increase again as aircraft use rises exponentially, and more land is opened up for agriculture using nitrogen-based fertilisers (see http://www.epa.gov/nitrousoxide/sources.html: accessed 31 March 2008)

[vii] Figures are superficially derived from a nice chart at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_carbon_dioxide_emissions, but have been cross-checked through the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, http://cdiac.ornl.gov/trends/emis/tre_coun.htm (accessed 5 March, 2008).

[viii] Based on figures from the World Trade Organization, http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/statis_e.htm (accessed 5 March, 2008)

[ix] Thomas Homer-Dixon, “The Upside Of Down”, Souvenir Press, 2007.

[x] Domestic trade (within the same country) figures are unreliable for the whole world, but even so, some explanation is needed as to why I have used international trade as an indicator instead. Between 1975 and 2000, total manufacturing output in the United States went up by 180 percent (based on figures from the US Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/indicator/www/m3/hist/m3bendoc.htm - accessed 10 March, 2008) to $1.9 trillion. In the same period, imports into the USA went up by 1100 percent (Based on figures from the World Trade Organization, http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/statis_e.htm - accessed 5 March, 2008) to $1.3 trillion – an increase more than five times that of domestic production. Given the powerhouse status that the USA still has in global economics, it is clear that international trade is a good indicator for the world economy after 1975.

[xi] Analysed in detail in: Keith Farnish, “Whose Carbon Is It Anyway?” The Earth Blog, http://earth-blog.bravejournal.com/entry/20579 (accessed 11 March, 2008).

[xii] We have looked at a number of them in Parts One and Two, such as the link between genetic modification and profit, and that between happiness and the consumption of goods. There is also the connection between the urgency for war and the desire by businesses to increase their profits, and a number of others that will become clear in Chapter 13. Very few of these social, political and economic connections are coincidental.

[xiii] Personal communication.

[xiv] No records exist earlier than about 600CE (see http://www.garhwalhimalayas.com/feel_garhwal/earlyhistory.html: accessed 13 March, 2008), but the nature of many tribes is that they leave no evidence of their existence except through oral histories.

[xv] Brian Nelson, “Chipko revisited - Chipko Andolan forest protection movement; India”, Whole Earth Review, 1993: accessed via http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1510/is_n79/ai_13805372/pg_1 (accessed 13 March, 2008)

[xvi] Quoted in Al Gedicks, “Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations”, South End Press, 2001.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] United Nations General Assembly, “Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the situation of human rights defenders, Ms. Hina Jilani. Addendum: Mission to Indonesia.” http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/refworld/rwmain?page=&docid=47baaeb62 (accessed 18 March, 2008)

[xix] See US State department reports for various years, e.g.: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61609.htm (“In February the Human Rights Commission in South Sulawesi concluded that the police committed a gross human rights violation in 2003 when they fired on farmers and indigenous persons attempting to reoccupy lands leased by the government to the London Sumatra Company; four persons were killed and more than a dozen were injured”) and http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2006/78774.htm (“During the year indigenous people, most notably in Papua, remained subject to widespread discrimination, and there was little improvement in respect for their traditional land rights. Mining and logging activities, many of them illegal, posed significant social, economic, and logistical problems to indigenous communities. The government failed to prevent domestic and multinational companies, often in collusion with the local military and police, from encroaching on indigenous people's land.”)

[xx] Quoted in Brian Halweil, “Home Grown: The Case For Local Food In A Home Grown Market”, Worldwatch Institute, 2001.

[xxi] Curtis White, “The Ecology Of Work”, Orion Magazine, http://www.orionmagazine.org/index.php/articles/article/267 (accessed 21 April, 2008)

[xxii] James Speth, transcript of speech made at The Brookings Institution, 16 April 2008, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/events/2008/0416_speth/20080416_speth.pdf (accessed 19 April, 2008).